The Civil War: Imagined and Real

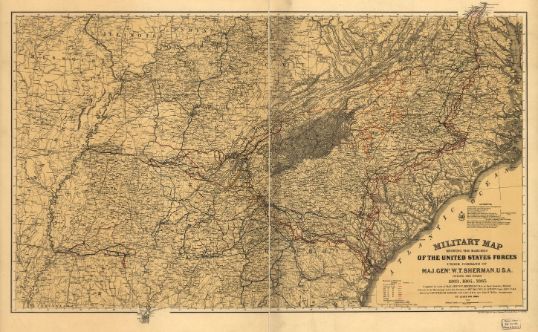

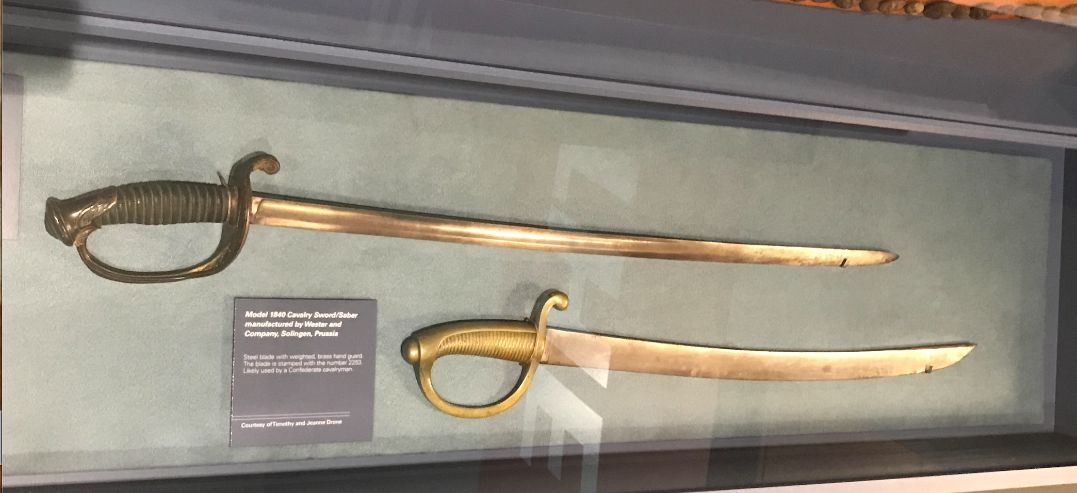

Timothy and Jeanne Drone’s recent gift of prints and artifacts serves as the inspiration for “The Civil War Imagined and Real.”

Their continued support inspires the imagination and enhances the learning of SLU students in a variety of disciplines. The exhibition “The Civil War Imagined and Real,” opened on September 28, 2018, and offers a great opportunity for multidisciplinary engagement. Activities such as lectures, tours, community partnerships, and interactive media projects related to the exhibition create opportunities for students of all ages to expand their knowledge.

Louis Kurz and Alexander Allison

Kurz & Allison Art Publishers

Chicago, Illinois

Louis Kurz was born in Austria and immigrated to the United States in 1848. He soon moved to Chicago where he made a name for himself painting sets for theater and opera houses. Kurz left Chicago after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and returned around 1880. Alexander Allison may have been a financial backer of Kurz & Allison Art Publishers.

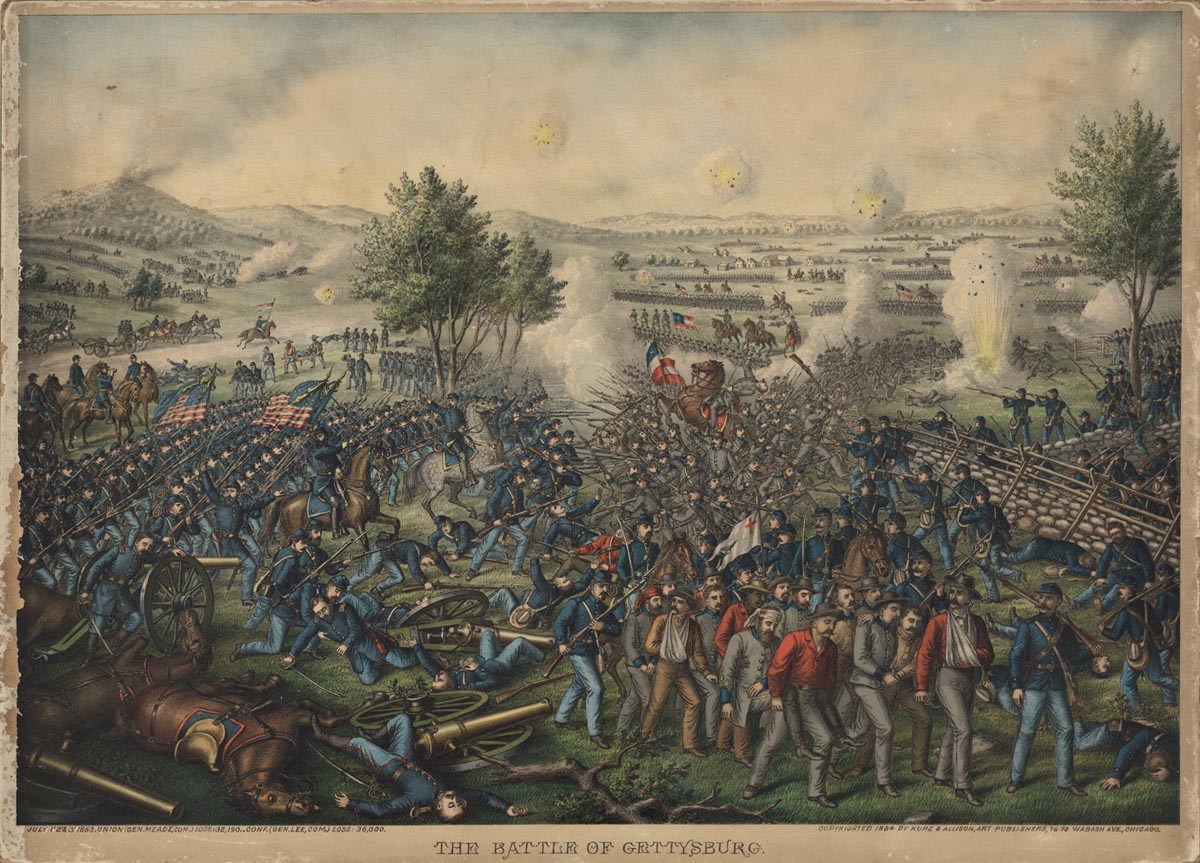

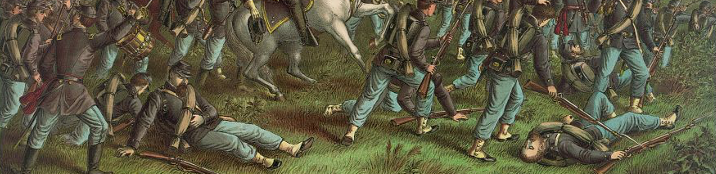

Kurz & Allison’s first chromolithograph, The Battle of Gettysburg, created in 1884, took inspiration from the exhibition of Paul Philippoteaux’s great cyclorama painting, a cylindrical, panoramic painting that created a 360 degree view of the battle for observers, which was exhibited in Chicago in 1883. The popularity of the painting may have inspired Kurz & Allison to profit from an appetite for visual images of the Civil War. They chose the most dramatic element of Philippoteaux’s painting, the failure of Pickett’s Charge on the battle’s third day, as the subject of their first chromolithograph and copied the erroneous depiction of General Armistead’s death including the “distinctive stone and rail fence angling to the vanishing point of the painting as well as the wounded prisoner being aided to the rear by two of his comrades in a basket- carry.” (212)

They also took inspiration from Louis Prang, a Boston printmaker, who published Prang’s War Pictures: Aquarelle Facsimile Prints in June of 1886. The popularity of Prang’s chromolithographs also showed that a huge market existed for Civil War images. However, the soon to be issued chromolithographs from Kurz & Allison lacked the artistry found in Prang’s work. Kurz & Allison chromolithographs, as historians Mark E. Neely and Harold Holzer have observed, “had a deliberately quaint appearance.”(216) The company’s chromolithography was more reminiscent of the work of antebellum American printmakers Currier & Ives than of Prang’s historically accurate depictions of the Civil War.

The chromolithographs were also “resolutely antiphotographic” (218), an interesting choice given the powerful and influential photographs of Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner (among others) that had become well known during the Civil War and which were well-represented in the unending volumes published about the Civil War in the late-19th century.

Viewers should not examine the Kurz & Allison Civil War chromolithographs and assume that they are seeing an accurate or realistic version of the battle presented. The prints are meant to evoke an emotional response. As the century progressed, the Great Rebellion lost many of its sharp edges. Yes, great armies massed in battle, cramped and noble. Soldiers attended to duty and officers exhorted to victory. There is struggle and sacrifice presented, but the horror experienced by the officers and soldiers is muted in the chromolithographs, and, instead, they illustrate romanticized memories of the Civil War suitable for a genteel home.

Source and page numbers refer to:

Mark E. Neely Jr. & Harold Holzer, The Union Image Popular Prints of the Civil War

North (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon is famously remembered for his capture of pro-Confederate militia under the command of General Daniel Frost at the Lindell Grove west of the city of St. Louis. Lyon accepted the surrender of General Daniel Frost and nearly 700 soldiers on May 10, 1861. Lyon’s action prevented the capture of the St. Louis Armory although most of its weapons and ammunition had been ferried across the Mississippi River to Illinois.

Lyon was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General and placed in command of the Army of the West, a small force of 6,000 officers and soldiers. Lyon was ordered to secure the state capitol and to prevent Missouri’s entrance into the Confederacy. After securing Jefferson City, the Army of the West then turned south and encamped near Springfield, Missouri. Soon, a Confederate force of 12,000 marched into Missouri from Arkansas. The Confederate force was under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch and was accompanied by a sizable force of the Missouri State Guard under the command of Major General Sterling Price.

Despite being outnumbered two to one, Lyon believed that moving aggressively would surprise the Confederates and give the Federal army an advantage. McCulloch thought the same and on August 10, 1861 the armies met in battle. Lyon’s men achieved initial success and then suffered two significant reversals: General Lyon was mortally wounded and regiments under the command of Colonel Franz Sigel mistook a regiment of Confederates, the 3rd Louisiana for the 1st Iowa regiment: both regiments wore gray uniforms. The Louisiana regiment advanced without resistance and led a devastating counterattack that forced a Federal withdrawal to Springfield. The battle is considered a Confederate victory.

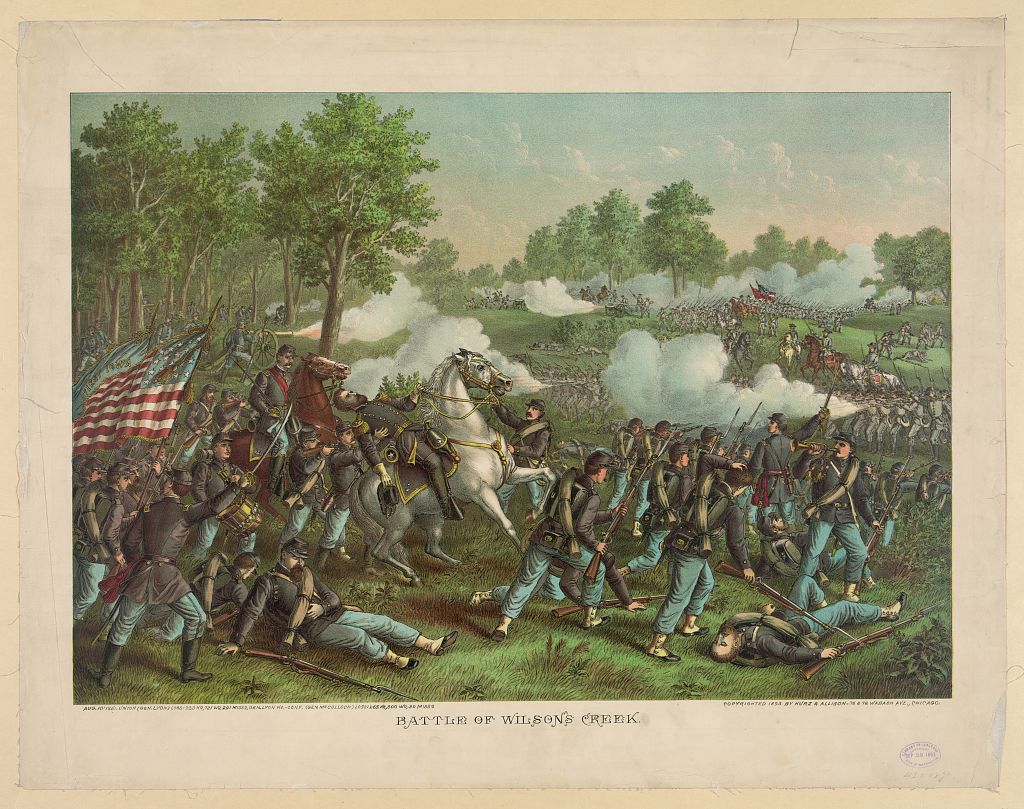

The Kurz & Allison lithograph shows the moment when General Lyon is mortally wounded. The battle is illustrated showing disciplined soldiers fighting in a manner more typical of later battles in the Civil War. In truth, the battle was characterized by inexperience and the confusion resulting from Lyon’s death and the severe wound that took his second in command, Brigadier General Thomas William Sweeny, away from the battle. George Whiting’s The Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri more accurately depicts the chaos of the battle and the mortal wounding of General Lyon.

Casualties:

1,317 Federal soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

1,232 Confederate soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon was the first Federal general to die in the Civil

War.

Following his victory in the capture of Fort Henry, Union commanding general, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, moved his forces to the Confederate stronghold of Fort Donelson. Donelson’s artillery commanded transit upon the Cumberland River and protected access to nearby Nashville, Tennessee.

Grant’s victory at Fort Donelson was the first major victory by Union forces in the Civil War and resulted in Union control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and, consequently, the states of Tennessee and Kentucky. Not long after the battle, Confederate forces abandoned Nashville, a major industrial center and the first state capital of the Confederacy to be lost.

Grant’s reply to the Confederate request for terms of surrender gained him considerable notoriety in the South and considerable fame in the North:

Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am Sir: very respectfully Your obt. sevt.

U.S. Grant Brig. Gen

Casualties:

Union losses were 2,691 (507 killed, 1,976 wounded, 208 captured/missing),

Confederate losses were 13,846 (327 killed, 1,127 wounded, 12,392 captured/missing)

Union forces under the command of Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis drove through southern Missouri with the intention of defeating the Confederate army under the command of Major General Earl van Dorn and to secure Union control of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. Curtis’ forces had been in pursuit of Major General Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard which retreated into Arkansas and then joined van Dorn.

Although outnumbered, Curtis forced battle with the Confederates. The two-day battle, fought in miserably cold temperatures, was a Union success, dependent upon Curtis’ effective use of artillery and the significant disruption caused by the deaths of many senior Confederate officers. Van Dorn was forced to retreat, and the Confederacy was not able to establish political or military control of Missouri for the remainder of the Civil War.

This battle was also notable for the participation of nearly 800 Native American soldiers who fought with van Dorn’s army, including the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles.

A notable inaccuracy in this image is the depiction of the Cherokee soldiers as Plains Indian warriors of the late 19th century, a depiction shaped by the popular media of the era.

Casualties:

Union losses were 1,384 (203 killed, 980 wounded,

201 captured/missing.) Confederate losses were around 1,100 (800 killed and wounded,

200-300 captured.) These losses included an unusual number of Confederate senior officers:

Generals McCulloch, McIntosh, and William Y. Slack were killed or mortally wounded.

Typical military strategy assumed that the capture of an enemy’s capital would lead to a swift end to a war. The proximity of Washington, D.C. to the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia – 95 miles– suggested that the primary goal of the Union’s Army of the Potomac was to battle on to Richmond. The army’s new commander, Major General George McClellan, accepted the maxim but determined a strategy that was innovative. Rather than driving his army south into the heavily fortified front before Richmond, McClellan, determined to take advantage of the Union navy, transferred the Army of the Potomac south of Richmond, landing his forces on the peninsula created by the James and York rivers. McClellan reasoned that he would take Confederate Major General Johnston E. Johnston by surprise and attack the Confederate capital through its far more vulnerable southern flank.

McClellan’s plan was brilliant, but his execution of the plan was slow and cautious. He believed that Confederate forces numbered nearly 100,000 men while the Army of the Potomac “only” numbered 130,000 men. Typical military planning of the day assumed that an army on the offensive required three times the number of soldiers as its opponents. McClellan landed his soldiers near the Confederate defenses at Yorktown. But instead of moving quickly to attack Yorktown which was defended by less than 15,000 Confederate soldiers, McClellan decided to lay siege.

This decision surrendered the element of surprise as well as his advantage in men and material. After a month, McClellan ordered an attack and the Confederates withdrew immediately a few miles north around the old Virginia capital of Williamsburg. The month-long delay resulted in the consolidation of Confederate forces so that there were nearly 56,000 Confederate soldiers available for the defense of Williamsburg.

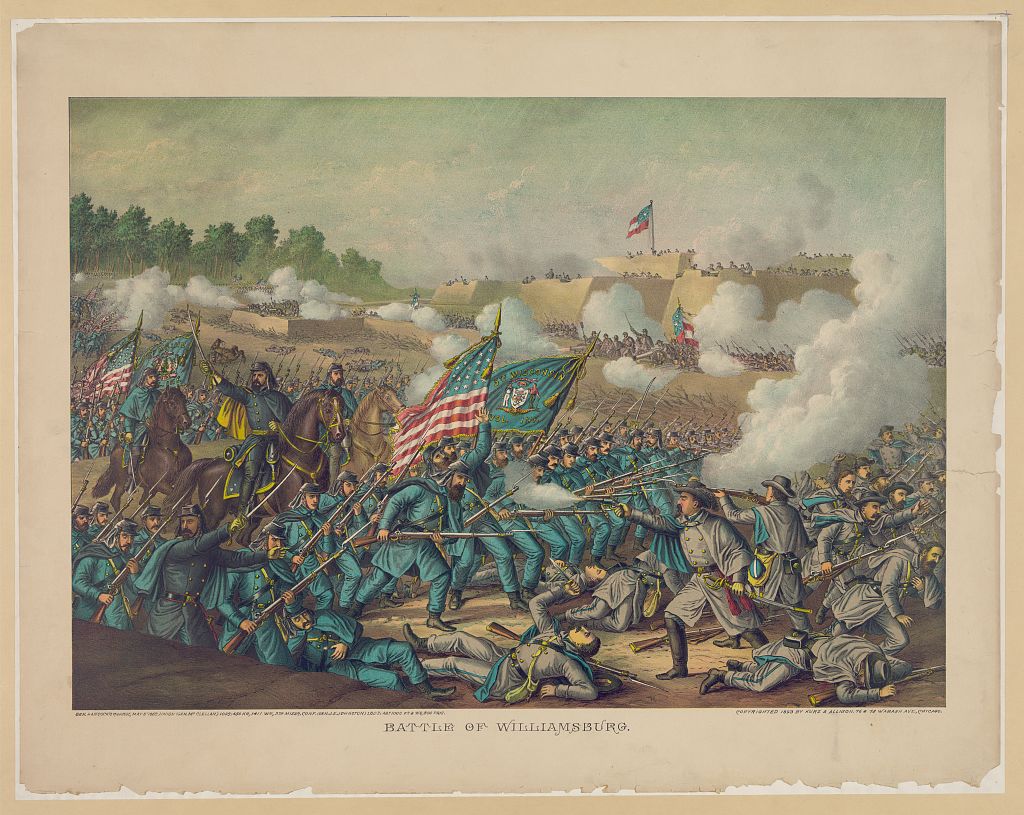

The Battle of Williamsburg was the first of the major battles of the Peninsula Campaign. A heavy rain fell throughout the day and the battle soon devolved into piecemeal engagements with neither side gaining advantage. Late in the day, information was received that the Confederates had left fortifications unmanned on their left flank. General Winfield Scott Hancock was ordered to take a brigade of infantry and artillery and occupy those fortifications. Realizing the threat to his line, Confederate Major General James Longstreet ordered Brigadier General Jubal Early to attack. Early’s attack failed and, in turn, Hancock ordered his men forward. The fighting was intense with the Union soldiers using their bayonets to force Early to retreat.

The battle ended at sundown. Longstreet withdrew under the cover of darkness to fortifications further north. General Hancock was lauded by McClellan who described his performance as “superb” and his performance was amplified in the national press. He would later play a significant role in defending the Union center, repelling Pickett’s Charge on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Hancock is shown in the lithograph as the mounted, sword wielding Union general encouraging the advance of Union infantry.

There is evidence to suggest that the Battle of Williamsburg’s significance was not military. Rather, this battle and the later battles of the Peninsula Campaign exposed Union soldiers to slavery as it existed in the south and demonstrated how the Confederate military used slave labor to augment their defenses, especially as Union soldiers witnessed slaves digging trenches and creating other fortifications, even under fire.

The Peninsula Campaign brought Union forces closer to Richmond than any time before 1865. Nonetheless, after a series of battles near Richmond known as the Seven Days Battle, McClellan withdrew his army to Harrison’s Landing on the James River. This retreat, coupled with the heavy losses incurred with no significant strategic advantage gained, was a significant blow to Union morale and a political nightmare for President Lincoln.

Casualties:

Union casualties were 2,283 killed, wounded and missing. Confederate causalities were

1,682 killed, wounded and missing.

The decision made by Robert E. Lee, commanding general of the Army of Northern Virginia, to bring his army into Maryland was driven by a belief that the people of Maryland would embrace the Confederacy and that Major General George McClellan, USA and the Army of the Potomac could be easily outmaneuvered and defeated.

This battle is notable for McClellan’s failure to take full advantage of the discovery of Lee’s battle orders – Special Order 191 – found on the ground wrapped around some cigars, which showed that Lee had divided his army and was all the more vulnerable if an attack occurred before Lee could consolidate his forces.

Antietam is considered one of the bloodiest, single-day battles of the war. Lee was forced to retreat to Virginia and Maryland rejected the Confederacy. McClellan was roundly criticized for his failure to attack Lee as he retreated, hampered as Lee’s army was by its great train of ambulances and wagons carrying the wounded. Lee was able to keep the core of the Army of Northern Virginia intact. President Abraham Lincoln would remove McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac, citing this failure, in November of 1862.

Lincoln understood Lee’s withdrawal as a strategic victory for the Union and used this battlefield win as an opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation which authorized Union armies to liberate slaves as a military necessity. The Proclamation also served to deter Great Britain and France from announcing formal alliances with the Confederacy.

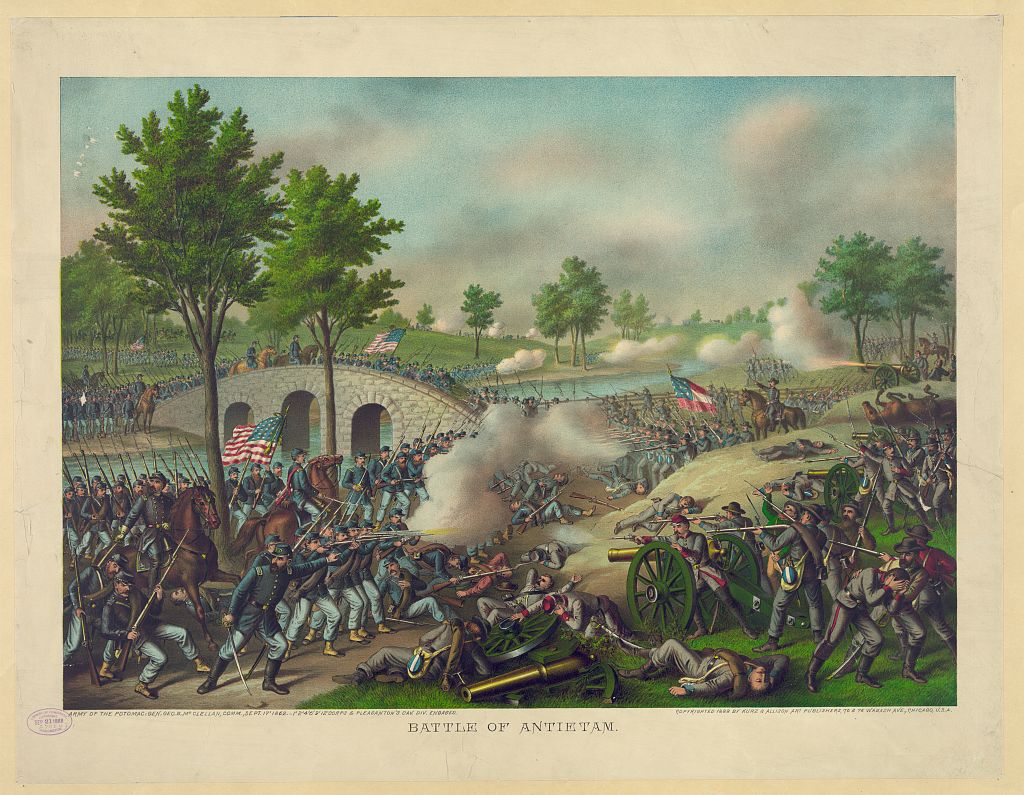

This Kurz & Allison image inaccurately depicts the crossing of Antietam Creek by General Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps. The Confederate soldiers did not abandon their positions to battle the Union soldiers near the bank of the creek. Instead, the Confederate forces, numbering around 500 soldiers, defended the assault from fortifications built into a bluff. This small force was able to hold off the Union attack for more than three hours.

Later historians, most famously Bruce Catton, would criticize Burnside’s tactics asserting that Antietam Creek was quite shallow and could have been easily forded. Concentrating upon the bridge was an ill-advised and dangerous strategy. More recent scholarship has determined that the creek banks were too steep, the water too deep, and the current too swift for a successful crossing of the creek without use of the bridge.

Casualties:

Losses from the battle were heavy on both sides. The Union had 12,410 casualties with

2,108 dead. Confederate casualties were 10,316 with 1,546 dead. This represented 25%

of the Federal force and 31% of the Confederate.

Major General Earl van Dorn, CSA commanded the Confederate Army of West Tennessee. He was ordered to break Union control of Corinth, Mississippi, a major railroad center and essential to control access into Tennessee and northern Mississippi. He ordered an attack against defending Union forces under the command of Major General William Rosecrans, USA. Rosecrans’ soldiers had occupied the abandoned Confederate trenches around Corinth.

The first day of battle was extremely hot and the outcome was inconclusive. Night brought the first day of battle to an end and opposing soldiers were separated by less than 600 yards.

The battle resumed on October 4 and, though van Dorn’s men were successful in entering Corinth, effective and deadly Union artillery fire drove the Confederates into retreat with heavy losses. The battle was effectively over by 1 p.m. Rosecrans was severely criticized for failing to pursue retreating Confederate forces. Van Dorn was criticized for surrendering the initiative he achieved in the first day of the battle. He was soon replaced by Lieutenant General James C. Pemberton who would later surrender Vicksburg.

The Confederate failure to regain control of Corinth ended the threat to Union communication and supply lines. General Ulysses S. Grant would soon begin his move upon Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River.

This color lithograph of the Battle of Corinth places all of the elements of the two-day battle into one scene, except for the fighting in the town itself. This battle was also notable for fierce hand-to-hand combat.

The artillery battery positions were nowhere near as substantive as depicted and they were not separated by the great distance as shown in the background.

Casualties:

Union forces reported 355 killed, 1,841 wounded, and 324 missing at Corinth for a

total of 2,520 casualties. Confederate losses were 473 killed, 1,997 wounded, and

1,763 captured or missing for a total of 4,233 casualties.

Despite the Union victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and the subsequent movement of Union men and material into Tennessee and Mississippi, this vast region was not free of Confederate activity. Consequently, a Confederate army commanded by General Braxton Bragg was sent to mid-Tennessee for the purpose of regaining control of the region and to impede the Union push to Vicksburg by threatening communications and supply.

The Battle of Stones River was a tactically inconclusive battle fought around the town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. However, it did result in a Confederate withdrawal from the battlefield and was counted as a Union victory – the first since the horrifying defeat of the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg, Virginia earlier in December of 1862. The ferocity of the Battle of Stones River resulted in some of the highest casualty numbers of the war in terms of ratio of soldiers dead to soldiers deployed.

This color lithograph is entitled inaccurately as the Battle of Stone River, rather than as the Battle of Stones River.

Casualties:

12,906 on the Union side and 11,739 for the Confederates. Considering that about 76,400

men were engaged and the total of killed, wounded or missing was 24,645, battlefield

losses were exceptionally high.

Following a stunning victory at Chancellorsville (April 30 – May 6, 1863), General Robert E. Lee decided to move the Army of Northern Virginia north into Pennsylvania with the idea of relieving pressure on Virginia’s war torn countryside and to achieve a victory on northern soil which might be enough to convince the British and the French to enter the war (finally) on the Confederacy’s behalf.

The Army of the Potomac was under the command of Major General George G. Meade who had taken command on June 30, 1863. Elements of each army blundered into one another at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania which sat upon the intersection of ten major roads, July 1, 1863. Sharp and bloody fighting ensued and both Meade and Lee rushed to consolidate their forces. Heavy fighting continued July 2 with Union forces taking defensive positions. The Confederates failed to dislodge them. On the third day of battle, having attacked both the Union left and right flanks, Lee mistakenly concluded that the Union center would be weak. This assumption would be proven untrue. Lee’s aggressiveness was illustrated by the infamous Pickett’s Charge of July 3. More than 12,000 Confederate soldiers marched over a half mile of rolling terrain to attack entrenched Union infantry and artillery at the center of the Army of the Potomac’s line. The charge failed to carry as Union fire took its toll and Meade was able to quickly move reinforcements to repel the charge.

The failure of the attack on the Union center led Lee to order retreat. The Confederate hospital train was more than 26 miles in length. The slow-moving retreat of injured and exhausted soldiers was ripe for attack, which President Lincoln demanded that Meade undertake. Instead, Meade demurred, asserting that his army was exhausted and weak and lacked sufficient ammunition and other necessary supplies to mount an attack. Lee was once again allowed to withdraw into Virginia with his army intact, though diminished.

This battle, coupled with the Union victory at Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, was decisive. Lee would not undertake another invasion and would fight defensively for the remainder of the war. However, the opportunity to bring the war to an end was missed and the Civil War continued for two more years.

While Meade retained command of the Army of the Potomac for the remainder of the Civil War, President Lincoln would soon promote Ulysses S. Grant to the rank of Lieutenant General and place him in command of all Federal armies. For the remainder of the Civil War, Grant would headquarter with the Army of the Potomac.

On November 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address as part of the service of dedication for the “Soldier’s National Cemetery” in Gettysburg. As historians have observed of Lincoln’s speech, he “reset” the struggle from that of a constitutional crisis to that of the nation’s obligation to fully embrace the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

This color lithograph of the Battle of Gettysburg was the first produced by Kurz & Allison and many historians believe that its creation was inspired by the popularity of the Gettysburg cyclorama which opened in Chicago in 1884. Not long after, a second Gettysburg cyclorama was opened in Boston. The Boston painting can now be seen (and experienced) when one visits the Gettysburg battlefield.

A cyclorama is a large-scale panoramic painting notable for its realism and, as the name suggests, is mounted upon a cylinder that is slowly rotated as visitors, standing in the center, look on. Presentations often included narration, sound effects, and music.

This Kurz & Allison image of Pickett’s charge on the third day of battle takes advantage of the popularity created by the exhibition of the Gettysburg cyclorama although the printers eschewed many of the elements of cyclorama artists. For example, this Kurz & Allison lithograph and the ones that followed made no pretense of photographic realism. The depictions tended to blend different elements of a battle into one scene and often possessed notable historical inaccuracies.

The Kurz & Allison Gettysburg image gives little indication that the 12,500 Confederate soldiers were spread out in a line of assault nearly one mile long. Federal soldiers fought behind fences and walls. Confederate officers advanced on foot with their men although Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead, CSA is shown falling from his horse after receiving his mortal wound

All this being said, this image of the Battle of Gettysburg was hugely popular with the public and the successful sale of the lithograph would lead, two years later, to a series of thirty-five additional Civil War color lithographs issued between 1886 and 1894.

Casualties:

Union casualties were 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured or missing.) Confederate casualties were 23,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing). Nearly a third of Lee’s general officers were killed, wounded, or captured. The casualties for both sides during the entire campaign were 57,225 out of the nearly 180,000 officers and enlisted men who were “present for duty” over the course of Lee’s invasion.

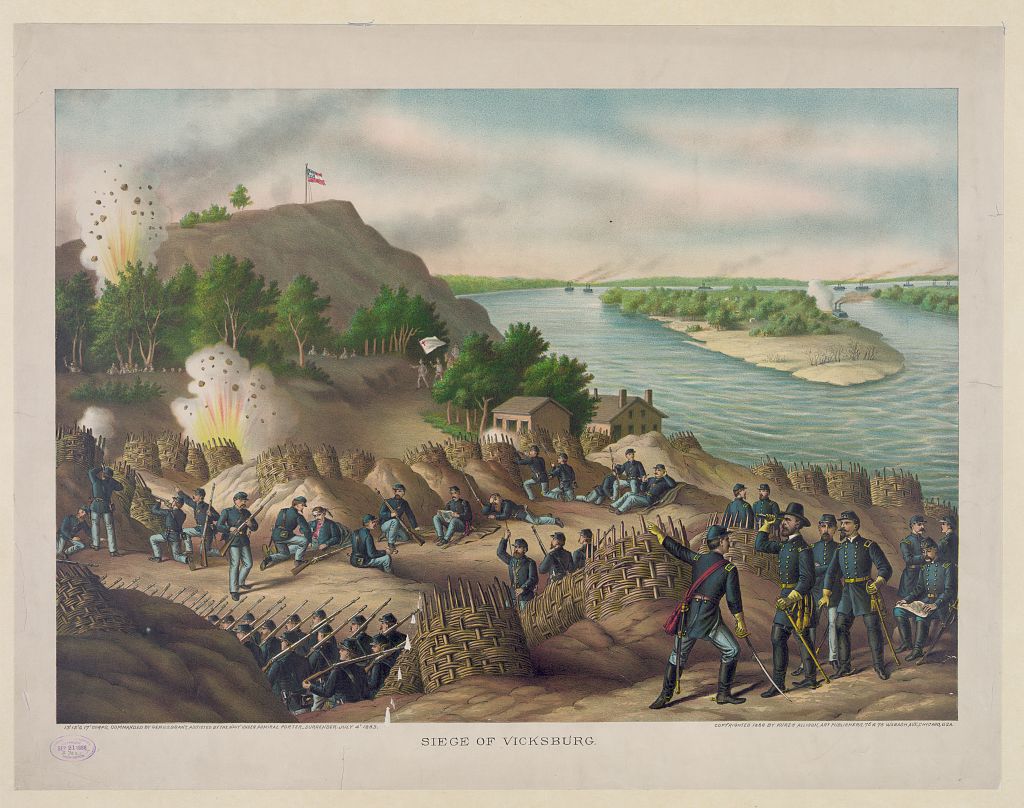

After a series of brilliant maneuvers, General Ulysses S. Grant forced Confederates troops under the command of Confederate General John C. Pemberton to consolidate behind the entrenchments of heavily fortified Vicksburg, Mississippi in May of 1863. After the failure of two deadly frontal assaults upon Vicksburg’s defenses, Grant determined to lay siege to Vicksburg. With the Mississippi River under the control of the Union navy, Pemberton had no way to escape the siege and he surrendered on July 4, 1863.

This was the second Confederate Army that Grant destroyed. As a result of the battle, Union control of the Mississippi River was unchallenged for the remainder of the Civil War. With this control, the trans-Mississippi states of Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas were effectively isolated and Texas would no longer serve as a major source of needed supplies, especially of goods crossing the border from Mexico.

General Grant is depicted in the lower right hand of the lithograph wearing the uniform of a Union general officer. He was famous for having little interest in the trappings of his rank and typically wore a sack coat tunic, which was standard issue for the enlisted ranks, with his rank as a major general depicted by a shoulder strap insignia. It is unlikely that he would have come upon the battlefield wearing the buff colored silk sash of a general officer and his dress sword.

Casualties:

Union casualties for the battle and siege of Vicksburg were 4,835; Confederate were 32,697 (29,495 surrendered). The full campaign, from March 29 to July 4, 1863 claimed 10,142 Union and 9,091 Confederate killed and wounded. In addition to his surrendered men, Pemberton turned over to Grant 172 cannons and 50,000 rifles to Grant.

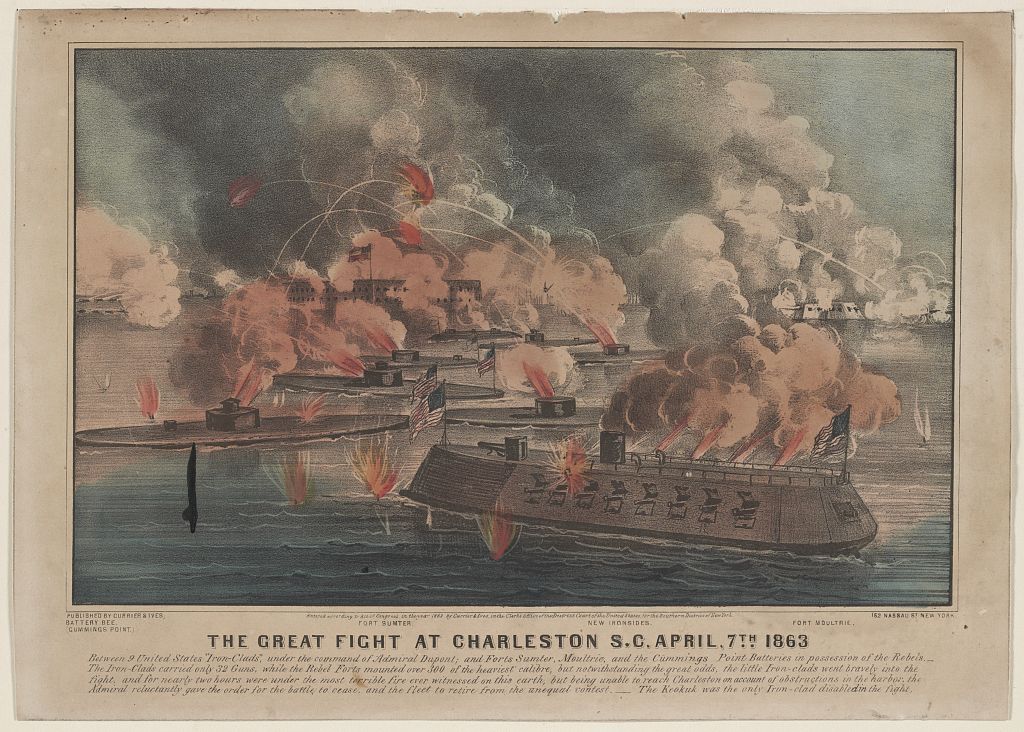

A Union fleet, which included nine ironclads, under the command of Admiral Samuel Du Pont, attacked Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863. Fort Sumter had been repaired and strengthened by Confederate forces. Their heavy guns, working in tandem with Confederate shore batteries, repelled the poorly executed Union attack. Although the ironclads could draw close to the fort, the Confederates had mined the harbor which limited their maneuverability. Du Pont’s fleet sustained 500 hits and the USS Keokuk, one of the ironclads, suffered so much damage that it sank the next day.

Morris Island in Charleston Harbor was occupied and fortified by Union forces in 1863. From September 1863 to February 1865, Union artillery pulverized the walls of Fort Sumter. The Confederacy, however, would not surrender the post until Union army forces, under the command of General William T. Sherman, attacked Charleston in 1865. On April 14, 1865, Major General Robert A. Anderson, who had been forced to surrender Fort Sumter in 1861, witnessed the raising of the same flag that had been lowered at his command four long years before.

President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated later that day.

Major General James B. McPherson was one of three Union Major Generals killed in the Civil War and the only general killed while in command of a Union army.

McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee was opposed by the Confederate Army of Tennessee under the command of Major General John B. Hood. Hood had recently replaced Joseph Johnston whose defensive maneuvers had slowed the Union advance on to Atlanta. Jefferson Davis sacked Johnston and replaced him with Hood as he felt that Hood’s aggressiveness would stop and then push back Union advances.

Hood lived up to his reputation. He initiated an offensive on July 22, 1864 having discovered that the Union 16th Corps and 17th Corps had drawn close to one another but had not joined tightly in the center of Union lines. Noting the gap, Confederate forces pushed into the center of Union lines and McPherson, concerned about the disposition of his forces, rode forward with an aide to see for himself what was happening.

McPherson’s curiosity proved fatal. He soon encountered Confederate infantry. In a hopeless position, he refused to surrender and, instead, attempted to turn his horse and ride to Union lines. He was shot and killed in the attempt.

Jefferson Davis received what he desired from General Hood. While Johnston had attempted to keep the Army of Tennessee intact through strategic maneuver, Hood instead flung his army at a numerically superior Union force of three armies that concentrated upon him. Hood failed and in defeat opened the way to Atlanta.

This lithograph depicts the general at the moment when he received his mortal wound. However, he was not surrounded by his soldiers on a battlefield.

Casualties:

Major General James B. McPherson

Commanding General, Army of the Tennessee

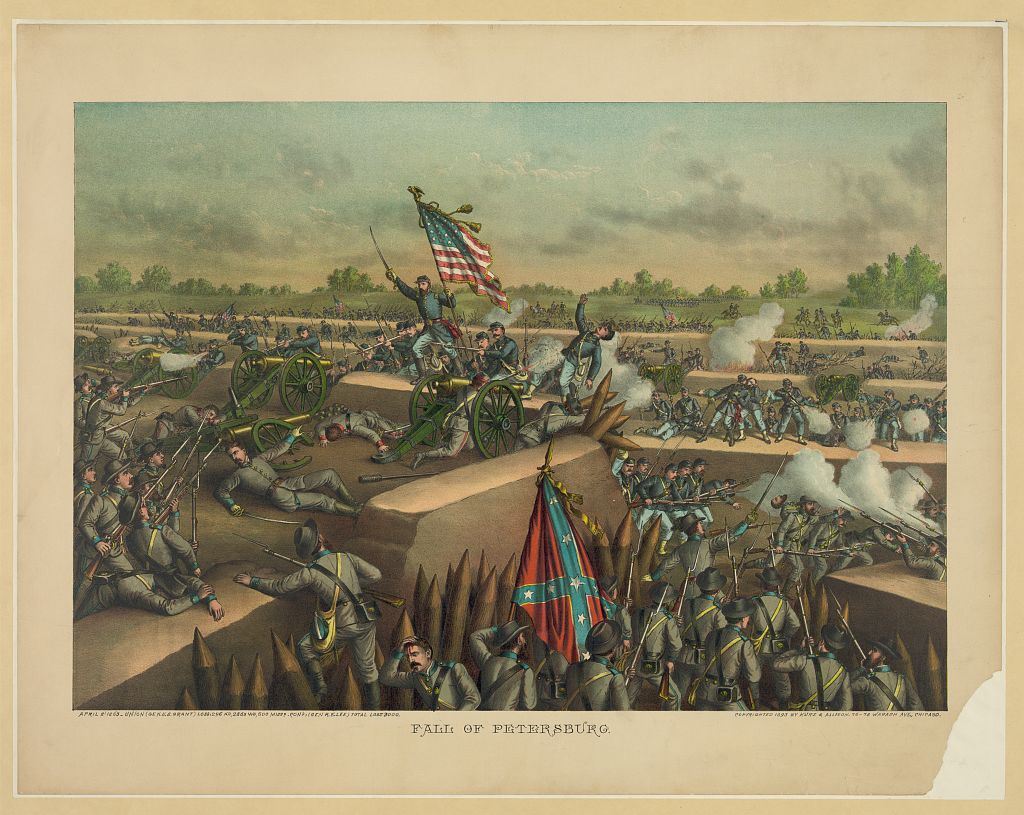

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia. It was not a classic military siege, in which a city is surrounded and all supply lines are cut off, nor was it strictly limited to actions against Petersburg. The campaign consisted of nine months of warfare which eventually resulted in the Confederate abandonment of Richmond.

Confederate defenses were stout. After a series of failed assaults, Union forces constructed siege lines and trenches that eventually extended over 30 miles from the eastern outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, to around the eastern and southern outskirts of Petersburg. Petersburg was crucial to the supply of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Numerous raids were conducted and battles fought in attempts to cut off the five railroad lines that ran through Petersburg.

The Siege of Petersburg foreshadowed the trench warfare that was common in World War I:

Casualties:

The initial assaults on Petersburg in June 1864 cost the Union 11,386 casualties,

and approximately 4,000 for the Confederate defenders. The casualties for the siege

warfare that concluded with the assault on Fort Stedman, March 25, 1865, are estimated

to be 42,000 for the Union and 28,000 for the Confederates. The Army of the Potomac

numbered at its peak in this campaign, 125,000 “present for duty.” The Army of Northern

Virginia numbered no more than 50,000 and by this time in the war, General Lee was

unable to replace his losses.

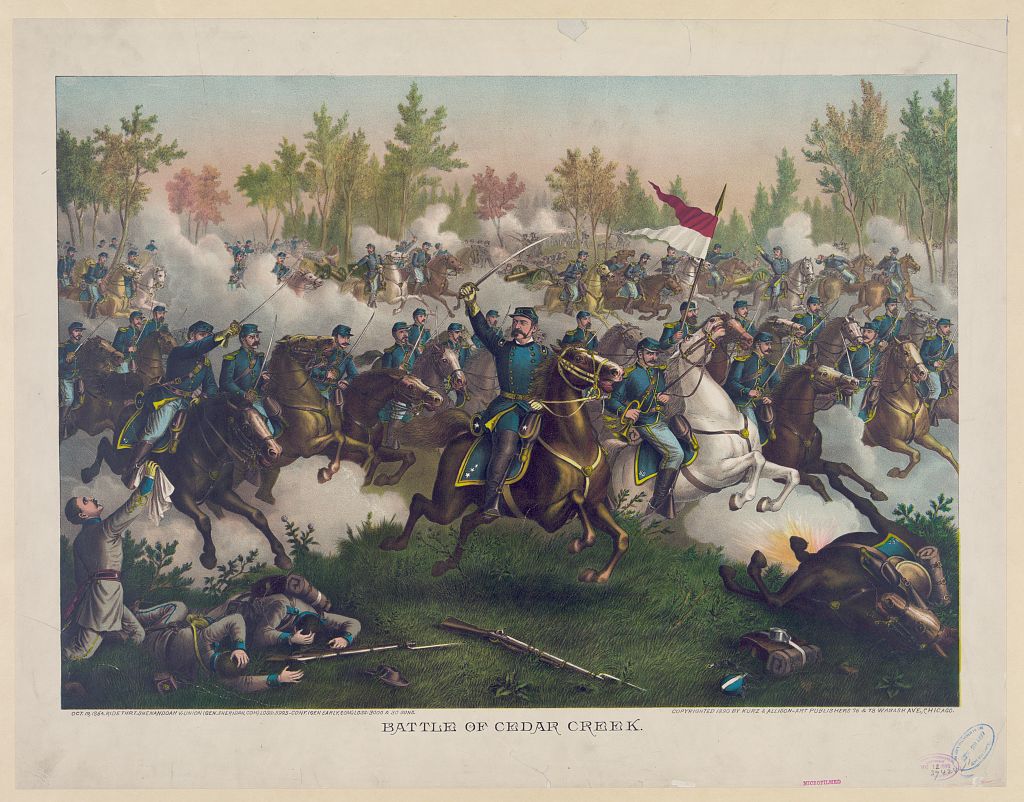

In an attempt to relieve pressure upon his Army of Northern Virginia (which was being slowly pushed into the defenses of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia), General Robert E. Lee ordered Lieutenant General Jubal Early, CSA to take a detachment of Confederate soldiers and cavalry into the Shenandoah Valley. This was the last invasion beyond the boundary of the Confederacy.

Lieutenant General Early found success and, most famously, attempted an attack against Washington, D.C., an attack that was witnessed by President Abraham Lincoln at Fort Stevens. Finding Washington to be too well fortified, Early then continued on into the Shenandoah Valley. General Ulysses Grant ordered Major General Phil Sheridan, Grant’s most capable cavalry officer, to engage in a series of battles known as the Shenandoah Campaign. Sheridan, conducted operations that stopped Early’s advance. Sheridan then ordered the destruction of grain and other supplies that were typically sent on to Richmond and to Lee’s army.

Early, a savvy general, realized that the disposition of Union forces had created an opportunity for a surprise attack which would negate the numerical advantage of Sheridan’s army. Unknown to Early, Union battlefield confusion would be magnified because General Sheridan was away in Washington, D.C. attending a meeting with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton at the opening of the battle.

Early’s offensive was initially successful. However, he wrongly concluded that he was facing a much larger Union force than anticipated and halted operations so that he could reorganize his army. This temporary stoppage allowed Early’s advantage to fade away.

When the attack commenced early the next morning, General Sheridan was encamped in the town of Winchester about 12 miles from the battle. The sounds of battle were clearly heard by Sheridan and he immediately mounted his horse and rode to the fight, encouraging his retreating soldiers to follow him and return to the battle. Sheridan’s men routed Early’s forces leading to a disastrous, unorganized retreat to Virginia. The victory at Cedar Creek was a major boost to President Lincoln’s bid for re-election in 1864.

Casualties:

Casualties for the Union totaled 5,665 (644 killed, 3,430 wounded, 1,591 missing).

Confederate casualties are only estimates, about 2,910 (320 killed, 1,540 wounded,

1,050 missing).

The battles before the trenches of Petersburg continued in late March of 1865 and culminated in the Battle of Five Forks, April 1, 1865. Union forces under the command of General Philip Sheridan attacked a Confederate force under the command of General George Pickett near the town of Five Forks, Virginia. Five Forks was key to the Army of Northern Virginia’s defense of Richmond as the South Side Railroad and the Danville Railroad lines ran through the town. Both these railroad lines, as well as major wagon roads, served as the only remaining supply route (and retreat route) for the army and the Confederate government.

The decisive unit in this battle was led by Union Brigadier General Romeyn Ayres although General Philip Sheridan would be remembered. As Ayres’ division moved forward, General Sheridan rode to the front of the line of battle, leading a charge into the Confederate ranks. Once again, Sheridan’s bravery and bravado made headlines.

The Union victory at Five Forks was followed on April 2 by a victory at the third Battle of Petersburg. General Lee was forced to withdraw from Petersburg and Richmond as they were no longer defensible. Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Courthouse came just one week later.

In this lithograph, General Sheridan is presumably the officer on the spotted horse seen in the center of the image. However, Sheridan’s horse was nearly as famous as he was. Rienzi, later renamed Winchester after the victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek, was jet black in color. Winchester can be seen on display at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History.

Casualties:

While there were casualties, the number of Union soldiers killed and wounded was small.

Confederate losses were low as well but for the capture of as many as 2,400 Confederate

prisoners.

The economies of Northern and Southern states developed divergently. The Northern states modernized and diversified rapidly. They developed expansive transportation systems which included roads, railroads, and steamboats. They also created strong financial industries (banks and insurance), and a large communications network, including newspapers, magazines, and the telegraph. By contrast, the Southern economy was based on commercial crops, such as cotton, and relied heavily on slave labor.

This divergence created different social, cultural, and political beliefs which led to disagreements on issues such as taxes, tariffs, internal improvements, and states’ rights versus federal rights. But the most contentious issue that led to the outbreak of armed hostilities was the growing friction over the role of slavery in American society.

The expansion of slavery into new territories was an issue since the late 1700s. Missouri’s request for statehood in 1818 sparked a heated debate between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups which ended in 1820 with the Missouri Compromise. The annexation of about 500,000 square miles after the 1848 Mexican-American War exacerbated the dispute over slavery.

After Lincoln’s election in 1860, seven Southern states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) seceded and formed the Confederate States of America. The attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, marked the beginning of the American Civil War, the bloodiest war in the history of the United States.

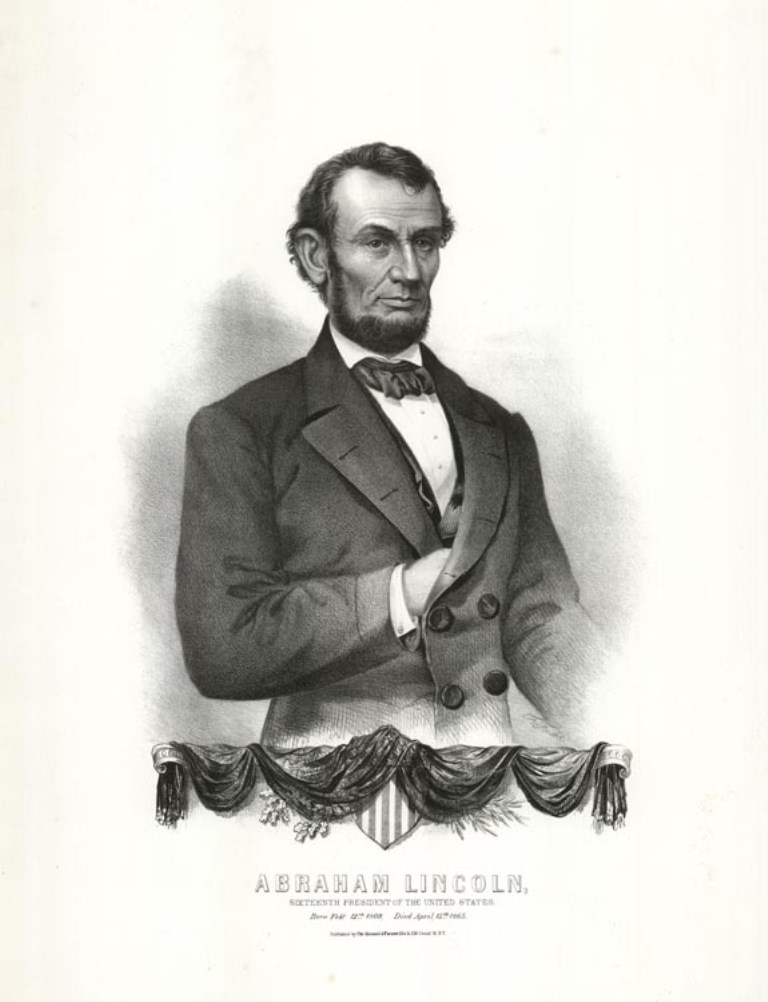

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865), born in Hardin County, Kentucky, was elected sixteenth president of the United States in 1860. At his inauguration, Lincoln denounced secession and discussed his desire to execute governmental laws in all of the states. He also pledged not “to interfere with slavery where it exists” and to enforce the constitutional provision for the return of fugitive slaves.

Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April of 1865 plunged Americans into deep mourning. This print, made in 1865, was based on a photograph taken on February 9, 1864 by Anthony Berger at Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C. gallery. The lithographer added the hand hidden within his jacket, which was considered a gentleman’s pose.

The Reconstruction Amendments

Following the Civil War, Congress created three amendments as part of its Reconstruction

program to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to black citizens.

Amendment XIII Abolition of Slavery (1865)

The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. It was passed by

Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865.

Amendment XIV Citizenship Rights, Equal Protection, Apportionment, and Civil War Debt (1868)

Passed by Congress on June 18, 1866, and ratified on July 9, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to all people “born or naturalized in the United States,” including formerly enslaved people, and provided all citizens with “equal protection under the laws.”

Amendment XV Voting Rights (1870)

Ratified on February 3, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited states from disenfranchising

voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, it

left open the possibility that states could institute voter qualifications equally

to all races. Many former Confederate states took advantage of this provision, instituting

poll taxes and literacy tests.

The Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution extended new protections to blacks, though the struggle to fully achieve equality would continue into the twentieth century.

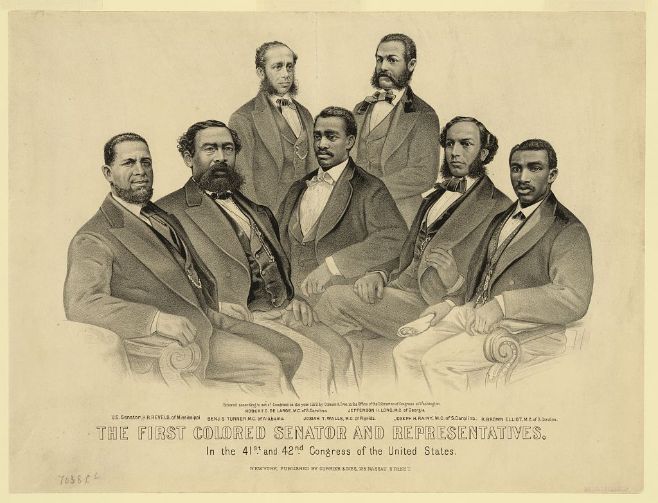

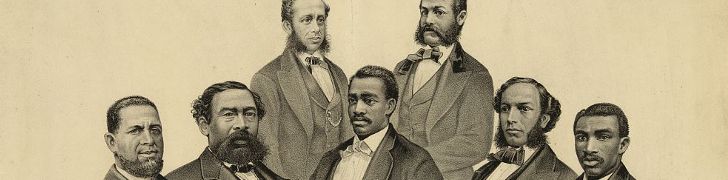

The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave the vote to all male citizens, regardless of color or previous condition of servitude. African Americans became involved in the political process not only as voters but also as governmental representatives at the local, state, and national level. Legislators pictured here are Senator Hiram R. Revels and Representatives Benjamin S. Turner, Josiah T. Walls, Joseph H. Rainey, Robert Brown Elliot, Robert D. De Large, and Jefferson H. Long.

Niépce’s associate, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, developed the daguerreotype process, the first commercially photographic process. The process consisted of coating copper plates with silver which were exposed to sunlight coming through the camera hole. Daguerre used mercury vapors to make the image appear on the plate. In the beginning, it took forty minutes to make a daguerreotype. At the time of the Civil War, it took only one minute of sitting very still.

Tintypes or ferrotypes, developed in the late 1800s, became very popular as they were sturdier and more affordable. The tintype was a photograph made by creating a positive image directly on a thin iron plate coated with a photographic emulsion. This technique was widely used between 1860 and 1870. Both daguerreotype and tintypes were used for portrait photography during the American Civil War.

Civil War photographers used glass plates to capture very sharp images. The cameras, which looked like wooden boxes, were very heavy. The photographers installed the cameras on wooden legs to keep them steady. A negative image was created when light hit the glass plate prepared with light-sensitive chemicals. On the glass negative, the light and dark areas of an image were reversed. Photographers then made multiple positive paper prints from the glass negatives. The glass plates had to be treated immediately after exposure. The treatment of the glass negatives and transferring of the images to paper required dark rooms. The Civil War photographers had to bring their dark rooms to the battlefield in horse-drawn wagons.

Samuel Abbott Cooley was born on November 3, 1821 in Hartford, Connecticut. His education and professional training are unknown. He operated a photography studio in Beaufort, South Carolina. In 1861, Beaufort was captured by Union forces during the Battle of Port Royal. Cooley photographed some of the earliest war images, and continued to document battles as a member of the U.S. Army’s X (Tenth) Corps. His wagon was equipped to successfully handle the on- site production of quality photographs.

Mathew Brady began his career as a portraitist. In 1844, he opened a studio on Broadway in New York City, where he photographed notable subjects such as Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adam, Abraham Lincoln, and others. Brady became the most famous American photographer of the 1800s after he secured permission from Lincoln for his staff of photographers to follow the Union Army in the field during the Civil War.

The photographers Brady employed worked under the direction of Alexander Gardner who managed Brady’s studio in Washington, D.C. Brady’s studio published the photographs taken by his employees under his studio name. Offended by the practice, at the end of the war, Gardner identified each of the eleven photographers in the two-volume publication Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1865–66).

Ruined by a series of financial setbacks, Brady spent his last years trying to sell his photographic archive to the American government. He believed that it would assist future artists in representing their subjects with greater authenticity.

At the start of the war, Southern photographers actively documented early confrontations through their images. Among them were J. D. Edwards and the team of Osborn and Durbec. It was also a Southern photographer who recorded the first images of the war inside Fort Sumter. The Union blockade produced an economic crisis that caused rampant inflation, putting most photographers out of business. As a result, far fewer photographs were taken by Confederate photographers during the American Civil War.

Only George S. Cook (1819–1902), the South Carolina-based photographer, continued to make and sell stereographs during the war. In 1863, he took two remarkable live-action shots of Union gunboats engaged in combat in the Charleston Harbor of South Carolina. These photographs were the first verifiable images of battle captured. On February 17, 1865 his Columbia, South Carolina studio was destroyed during a firestorm. Cook moved with his family to Richmond, Virginia in 1880 where he bought up the businesses of photographers who were retiring. He created the most comprehensive collection of prints and negatives of the former Confederate capital known to exist.

Southern photographer, J.D. Edwards (1831–1900), undertook one of the earliest wartime photo expeditions in April of 1861. He followed Confederate units from New Orleans to Pensacola, Florida, as they mobilized against Fort Pickens. In June of the same year, two of his photographs were reproduced as woodcuts in Harper’s Weekly, but he received no credit for them.

The attitude toward war photography was extremely unfavorable in the South after the Civil War, and many photographs were disposed of. The only ones that survived were family portraits of Confederate servicemen.

George Smith Cook, born in Stratford, Connecticut in 1819, moved south at the age of fourteen. By 1849, he had settled in Charleston, South Carolina and established himself as a master of his photographic craft. Two years later, Mathew Brady asked Cook to manage his New York gallery while Brady traveled to Europe. While managing Brady’s gallery, Cook opened a gallery of his own in New York. When Brady returned in the spring of 1852, Cook closed his New York gallery and returned to Charleston. He later opened galleries in Chicago (1857) and Philadelphia (1858).

At the beginning of the Civil War, Cook closed his galleries and concentrated on events

in Charleston. He became “the photographer of the Confederacy,” producing photographs

that rivaled Brady’s in their excellence.

During the Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter in August and September of 1863, Cook

produced truly outstanding photographs showing the devastation caused by the Federal

batteries.

After the end of the Civil War, George S. Cook continued as a studio portraitist until his death in 1902. A collection of Cook’s photographs is now maintained by the Valentine Museum in Richmond, Virginia and consists of over 10,000 photographs.

Throughout the American Civil War, Northern photographers were officially embedded within the Union Army. By the end of the war, they captured more than seven thousand images of unprecedented death and destruction. These photographers set to objectively capture the realities of war. However, in some images it becomes apparent that they inserted their own views of the history they lived.

Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, George Barnard, and photographers that worked for their studios, stand out for influencing how generations of Americans formed their understanding of the Civil War.

Mathew Brady was the first photographer to travel to the front lines. Although Brady secured the permissions necessary to document the Civil War early on, photographers working for his studio actually brought him success by photographing iconic images. Brady recognized the talent and expertise of Alexander Gardner and hired him in 1856 to work for his studio in New York. Two years later, Gardner was managing Brady’s Gallery in Washington, D.C. Gardner was an expert in wet-plate collodion photography, and in the “Imperial Print”, a 17 by 21 inch enlargement, which made Brady famous.

By 1863, Alexander Gardner and his brother opened their own studio in Washington, D.C., taking with them many of Mathew Brady’s staff. The split was caused by Brady’s lack of business acumen and failure to regularly meet his payroll. After the war, Alexander Gardner published his Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, which included images by other photographers, such as Timothy O’Sullivan, James Gibson, George Barnard, James Gardner, and William Pywell, who followed the armies and recorded the American Civil War.

While Brady, Gardner, and other photographers set to objectively capture the realities of war, they could not escape the complex political role photography played in shaping public opinion.

The technical limitations of photography to capture epic scenes of battle in color and in real time created a big demand for lithographs. The colorful battlefield lithographs mass- produced by Louis Kurz and Alexander Allison and by Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives captured the imagination of the American public.

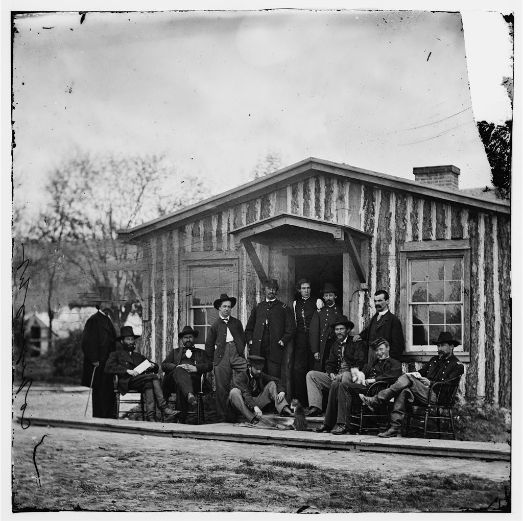

This photograph was taken in the main Eastern Theater during the Siege of Petersburg, between June of 1864 and April of 1865. Photographer Mathew Brady can be seen in this photo, standing at far left. Before the war began, Brady created studio portraits of Union generals in his New York and Washington, D.C. galleries. When the war began, he was already one of America’s foremost portrait photographers.

Mathew Brady assembled teams of photographers and secured permission for them to accompany Union forces in the field. As a result, his studio produced a comprehensive visual record of the Civil War.

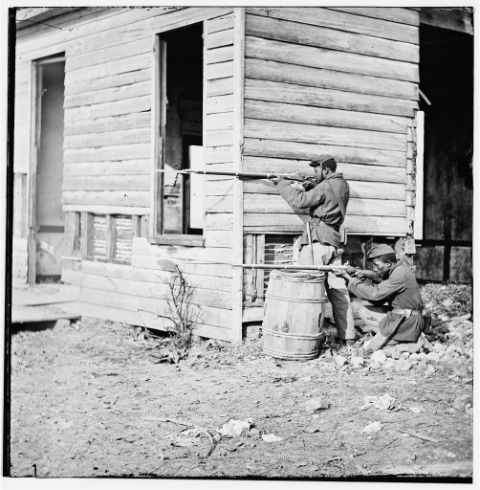

After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, free black men rushed to enlist in U.S. military units. They were denied because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred them from bearing arms for the U.S. Army.

The Lincoln administration was concerned that the recruitment of black troops would prompt the border-states to secede. By mid-1862, the number of white volunteers declined, and the needs of the Union Army increased. This prompted the Government to reconsider the ban. On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army.

Recruitment was slow until March of 1863, when two of the nation’s leading African-American statesmen, Frederick Douglass of Rochester and Jermain Loguen of Syracuse, called men to arms. Enlistees included two of Frederick Douglass’ own sons. In May of 1863, the Government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage the increasing number of black soldiers who answered the call.

State and federal regiments at the time were comprised of 200,000 black soldiers. There were nearly eighty black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman, who scouted for the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers.

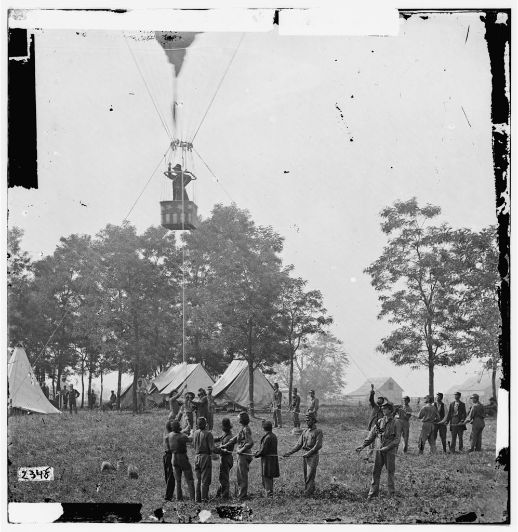

Increasing technological advances in the early nineteenth century accelerated the start of the Civil War. In 1783, French inventors made balloons capable of carrying people in attached baskets. The first balloons relied on hot air to rise, but soon used hydrogen as a compact alternative. Both sides used balloons for aerial reconnaissance, mapping, and for gathering intelligence about the enemy. A Balloon Corps was established by President Lincoln and the first official Union balloon launch occurred in late August of 1861. Balloon operators used the telegraph to let commanders on the ground know of Confederate movements. This allowed Union guns to be repositioned and fired accurately at troops more than three miles away – a first in military history.

Intelligence was crucial to winning the war. The U.S. Army Signal Corps was established shortly before the start of the Civil War. The South established the Confederate States Army Signal Corps which included the covert intelligence agency known as the Secret Service Bureau. The North’s technological advances were often hampered by political disputes in Washington between the Union Signal Corps and the civilian-led U.S. MilitaryTelegraph Corps.

Both sides participating in the Civil War used technological advances to gain advantages over the other. This is why many believe the Civil War was the first modern war. The industrialized North had a clear advantage over the South, and the gap grew larger as the war continued.

On June 17, 1861, Thaddeus Lowe dictated to a telegraph operator by his side: “The city…presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station…”

Lowe was in a gas balloon tethered 500 feet above the Columbia Armory in Washington, D.C. The telegraph cables were connected to the War Department. The man receiving the message was President Abraham Lincoln. Despite its success, the Union’s Balloon Corps disbanded in 1863. Aerial reconnaissance was one of the new technologies by both sides.

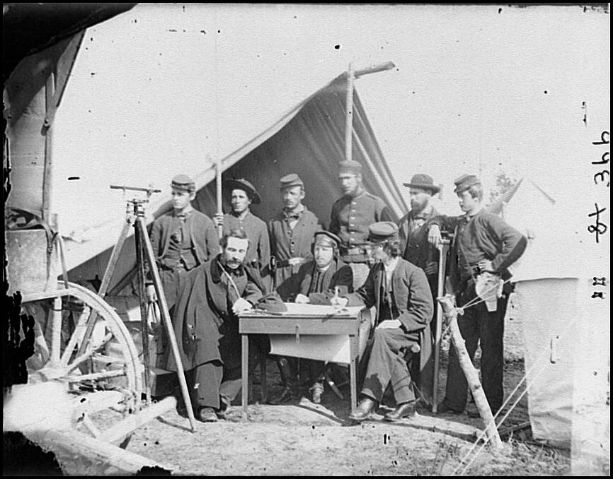

This photograph was taken in the main Eastern Theater of the Civil War during the Peninsular Campaign, between May and August of 1862. The photo shows a group of nine men posed in front of a tent with a surveying instrument to the left. The two men seated center and right are most likely Frederick W. Door, who produced the famous map the Battle of Chattanooga, and John W. Donn. The officer seated to the left is William H. Paine, who invented the steel tape reel worn by the man standing on the right. Allan Pinkerton, detective and spy known for the establishment of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, appears to be standing second from the right.

Though much has been written about the Civil War, little has been written about the spying that occurred. Union intelligence records were kept sealed in the National Archives until 1953. Even today, the identities of many spies remain secret.

In the Civil War, both sides used traditional intelligence techniques, such as code- breaking, deception, and covert surveillance. Two innovations emerged, however, that would endure as tools of espionage: wiretapping and overhead reconnaissance. In 1863, an official Federal intelligence unit emerged. Spies on both sides worked as anonymous agents and false deserters. They were dispatched to relay false information to the enemy.

Samuel Morse (1791-1872), inventor of the telegraph and Morse code, sent his first message over the wires in 1844. Morse code allowed for the transmission of complex messages across telegraph lines. Morse’s inventions revolutionized long- distance communications.

During the war, 15,000 miles of telegraph cable were laid by the North. Between May 1, 1861 and June 30, 1865, the USMT (United States Military Telegraph) handled approximately 6.5 million messages. The telegraph increased the speed at which news about the war reached the public and played an important role in the North’s victory.

By contrast, the South had a much smaller telegraph network. The Confederate Government placed telegraph lines under martial law and the blockade contributed significantly to their lack of supplies.

The military telegraph network proved its value in coordinating broad strategy during the war. The North’s technological advantage over the South contributed to its victorious outcome.

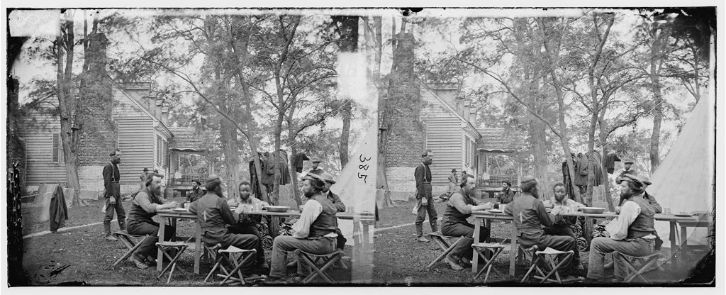

This photograph, from the main Eastern Theater of the war, shows the winter quarters at Brandy Station, between December of 1863 and April of 1864. The Union particularly saw the value of the telegraph and used it as the key component in what would be the first modern military communication system. The Confederacy also used the telegraph for tactical communications in the field.

This photograph, from the main Eastern Theater of the war, was taken between June of 1864 and April of 1865. For most of the war, Union Army telegraphic messages were handled by the civilian-staffed U.S. Military Telegraph (USMT), which connected battlefields with far-flung generals and with the War Department in Washington. Field telegraph units that linked commands and were connected to hilltop signalers who sent messages by flags during the day and by torches at night.

The American public and political leaders were fiercely opposed to peacetime armies and resisted paying for or maintaining them. As a result, the antebellum military consisted of volunteer militias.

The Corps of Engineers, a permanent branch of the Army established by Thomas Jefferson at the same time as West Point in 1802, was always undermined by a lack of public and governmental support.

In peacetime, the Corps of Engineers built bridges and roads, oversaw lighthouses, managed the country’s permanent fortifications, explored the frontiers, protected the borders, and maintained infrastructure. In wartime, the Corps of Engineers led volunteer infantry on the battlefield and lent their expertise in tactical thinking, defensive positions, and topographical knowledge.

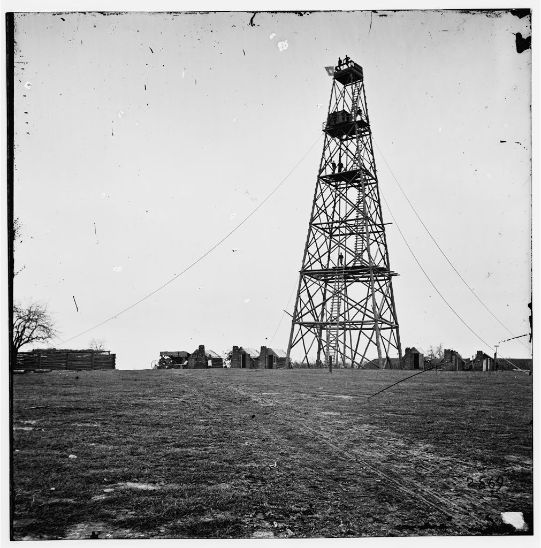

At the beginning of the Civil War, many engineers enlisted in the volunteer army in various states. The ones that remained with the Corps of Engineers constructed Washington, D.C’s impenetrable ring of defenses, collectively known as the Defenses of Washington.

To maintain the high level of his personnel’s expertise, Chief Engineer Joseph Totten increased recruitment from West Point. Despite his efforts, he was very short on personnel throughout the war.

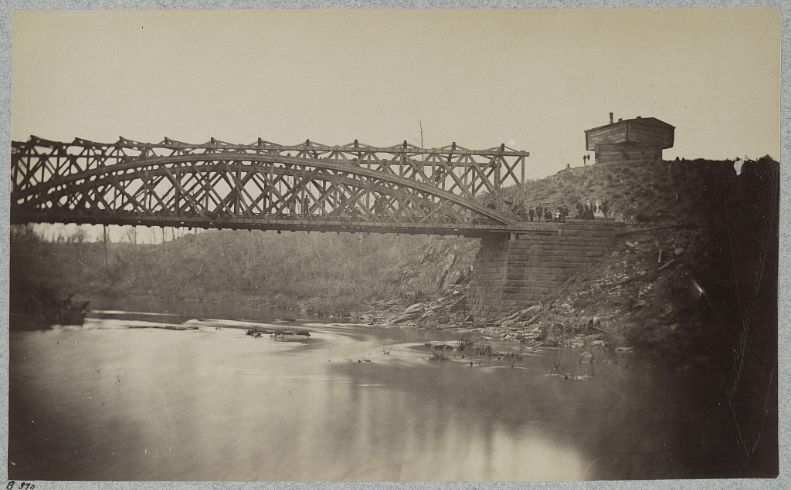

Despite the hardships, the Corps of Engineers played a pivotal role on the Eastern Theater and made major contributions to the outcome of the war. They built pontoon bridges and twenty-five miles of entrenchments around General Robert E. Lee’s position at Petersburg that eventually forced Lee to flee and later surrender.

The United States Military Railroad was a military organization whose role was to support the Union Army wherever it needed. In the field, that meant repairing tracks and replacing bridges. Daniel McCallum, the United States Military Railroad’s head, was a railroad expert. He created a substantial and well-equipped railroad shop complex at Chattanooga in support of the Atlanta Campaign and Sherman’s March to the Sea.

The pontoon bridge is a basic, easy to build structure consisting of multiple floating components linked together. The most important component of this bridge was the float or pontoon. This type of bridge had no piers or any other type of permanent under supports. No nails were used in its construction; everything was assembled to make the bridge easy to build, dismantle, move, and reuse.

The Orange and Alexandria Railroad played a pivotal role in the Civil War. It was

the only rail link between the capitals at Washington, D.C., and Richmond, and it

was fought over by both Union and Confederate forces.

A primary objective of the Construction Corps was to repair damaged railways quickly

to keep supply lines open, and to transport soldiers. Due to the challenges associated

with defending numerous railroad bridges, the repair and replacement of bridges was

frequent. Simplicity of design was more important than durability for military bridges.

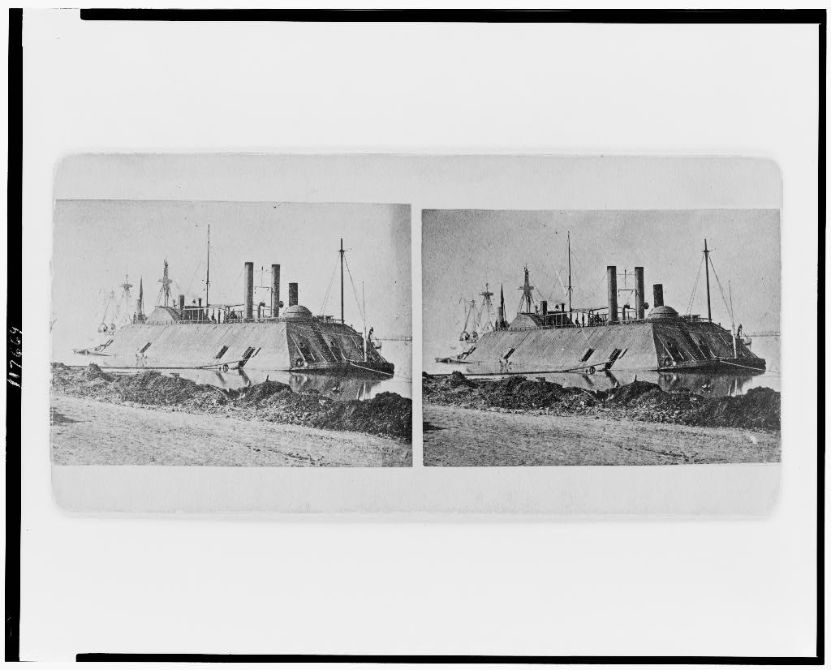

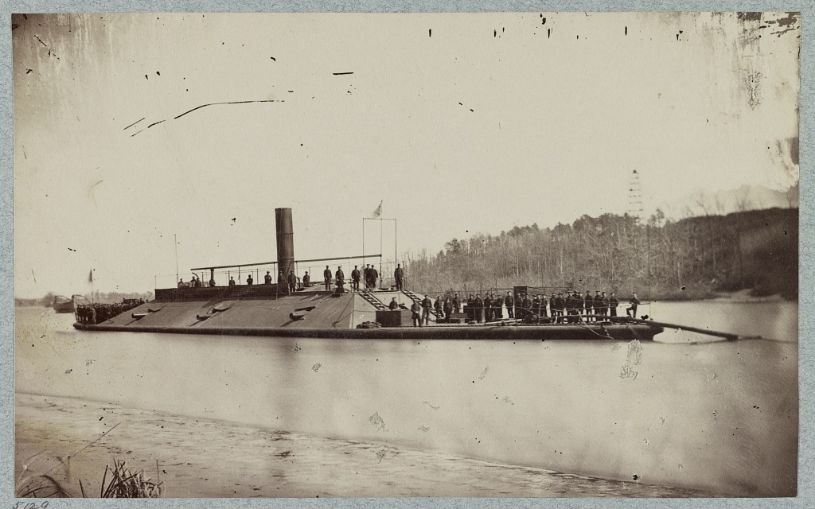

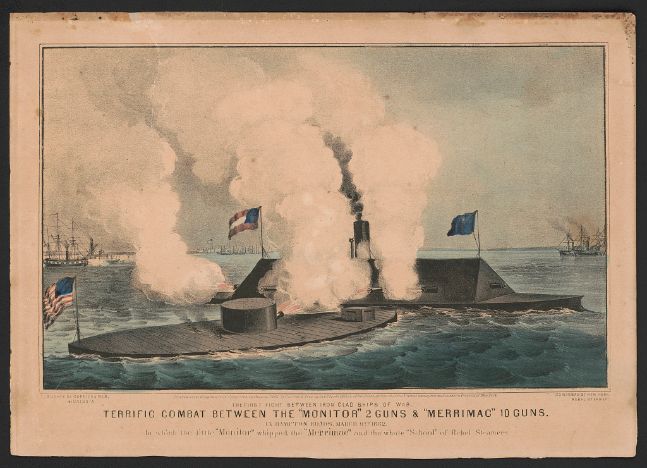

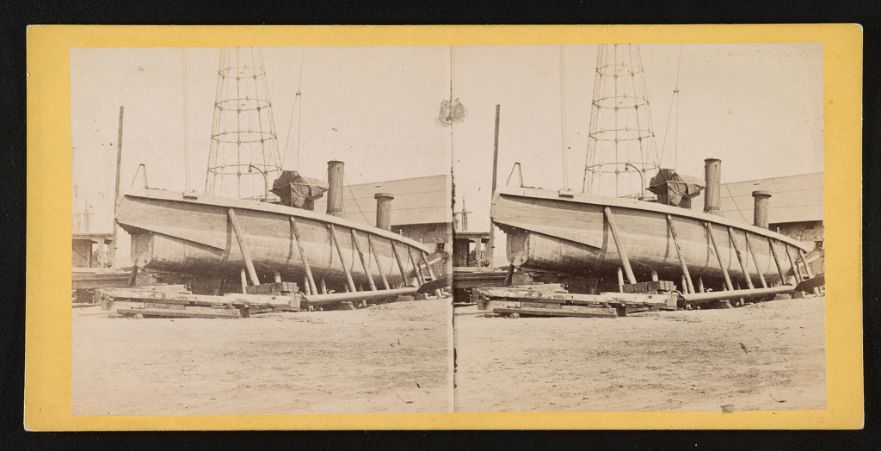

The ironclad was an armored warship first used in the Civil War. The development of steam-powered warships and of large-caliber rifled cannons in the mid-nineteenth century made armoring necessary. The ironclads revolutionized warfare and demonstrated their superiority during the American Civil War. Both the Union and Confederate navies rushed to build ironclad ships to counter each other.

The Confederates covered the hull of the scuttled steam frigate, USS Merrimack, with iron armor four inches thick, and renamed it CSS Virginia. To counter the Virginia, the Union built the USS Monitor, an innovative vessel with a rotating gun turret. On March 9, 1862, the ironclads met in battle for the first time at Hampton Roads, Virginia. The two fought to a draw.

The Virginia was destroyed to prevent a capture by Union forces, and the Monitor sunk in a storm off North Carolina. The Union built fifty more Monitor-class ironclads, which were invaluable in winning the war.

After the Civil War, there was little need for ironclad vessels, as very few of them were seaworthy. The majority were scrapped for iron. In the late nineteenth century, improvements in the steelmaking process ended the need for ironclad vessels. Rather than using a wooden hull with armor only above and a few feet below the waterline, the entire ship could be made from steel. Nonetheless, ironclads were a crucial innovation in the history of naval warfare.

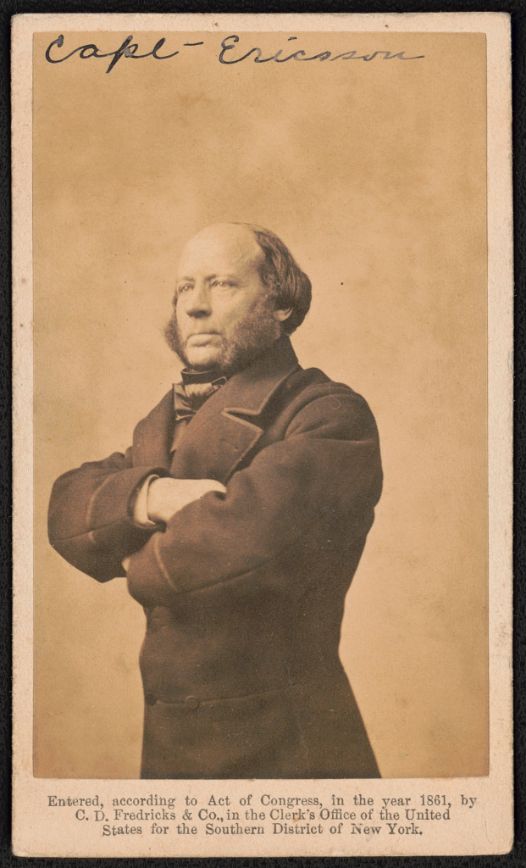

John Ericsson was born and raised in Sweden and immigrated to America in 1839. By the time he came to the U.S., he was well-known for developing the marine screw propeller, the caloric engine, and the history-making turret. In 1861, he signed a contract with the U.S. Navy to build an ironclad vessel. At the outbreak of the Civil War, both the Union and Confederacy began experimenting with ironclad warships. His achievements revolutionized naval warfare and earned him international recognition.

James B. Eads was born in Indiana and moved to St. Louis as a boy. He built the bridge over the Mississippi in St. Louis that bears his name. Eads promised President Abraham Lincoln he could build iron-armored gunboats in sixty-five days.

On Aug. 7, 1861, Eads won a contract to build seven gunboats, each carrying thirteen heavy cannons, and having 2.5 inches of armor. His ironclads were 175 feet long and squat, with sloped wooden sides covered by iron plate. Five long boilers powered the engines for a single paddle-wheel. Eads built four at Carondelet and three at Mound City, Illinois, near Cairo. He delivered all seven by mid- November and paid penalties for the delay.

The confederate ram Atlanta was an ironclad that was converted from a Scottish-built blockade runner. After several failed attempts to attack Union blockaders, the ship was captured by two Union monitors in 1863, and served in the Union Navy for the rest of the war. It was deployed on the James River and served the Union forces there. The ship was decommissioned in 1865.

The military experienced great progress during the Civil War. Its arsenal included torpedoes, submarines, and ironclad ships. The best- known ironclad ships were the Confederate Merrimac and the Union Monitor. On March 9, 1862 the Monitor, which was faster and easier to maneuver, and the Merrimac which was bigger, stronger, and carried more guns, fired their cannons back and forth in an epic battle that lasted for several hours. The battle ended as a draw. Currier & Ives capitalized the clash between the Monitor and the Merrimac, issuing three versions of the battle.

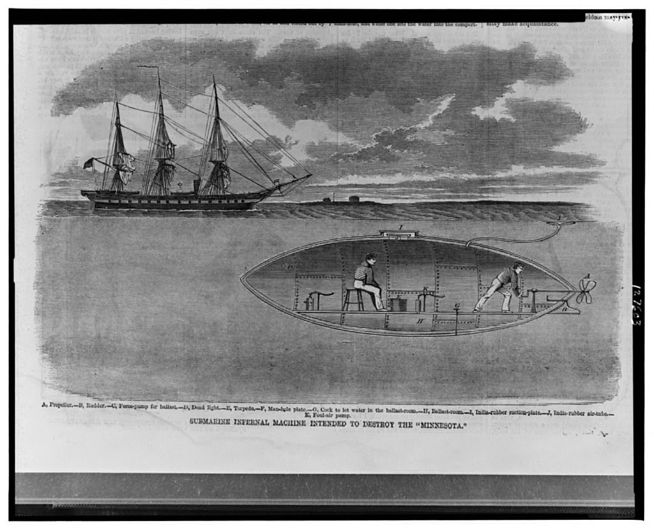

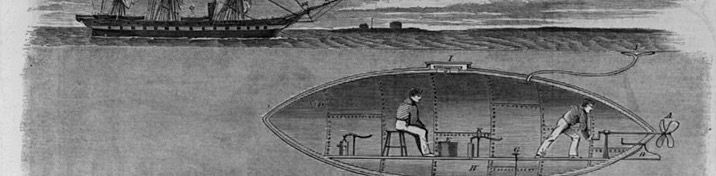

While submarines were first built in United States during the Revolutionary War, they were explored again during the American Civil War. In 1861, Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson developed the CSS Pioneer. It was sunk before combat to prevent its capture by Federal forces. The Confederates also built small, steam-powered submarines, called Davids.

In 1861, the Union Navy hired a French inventor to build a submersible warship. On May 1, 1862 the Alligator became the first submarine of the U.S. Navy. In 1863, it was sent to Charleston, South Carolina but was lost during a storm.

Other attempts to use submersible vessels were made by both warring parties. However, most accounts of using submarines during the American Civil War focus on the sinking of the ironclad USS Housatonic by the CSS H. L. Hunley in 1864. This was the first time a submarine destroyed an enemy ship in combat.

During the American Civil War, Confederate torpedoes inflicted heavy losses on the Union Navy. This experience prompted the Union Navy to design and build vessels capable of using this new weapon. This led the Chief Engineer of the United States Navy, Captain William W. Wood, to design a screw steam torpedo boat called Spuyten Duyvil.

Submarine warfare was considered almost illegal, with the term “infernal machine” used liberally in Northern reports. Because of this, records relating to submarines and underwater mines were intentionally destroyed toward the end of the war to keep the identities of those involved secret. The North, while publicly denouncing undersea warfare, engaged in its own building program and thus had good reason to keep most references out of the Official Records. The few that survive repeatedly insist upon secrecy.

Civil War weapons played a critical role in deciding many battles. During this period, great advances were made in the rifle, musket, cannon, and bullet, including the Minié ball. The Union artillery had a strong advantage. It had extensive manufacturing capacity, and a well- trained artillery branch. The South was at a disadvantage as a Union blockade prevented foreign arms from reaching Southern armies. As a result, the Confederacy relied on captured Union artillery pieces and captured armories.

One of the new ammunitions used in the Civil War was the grapeshot, which consisted of small metal balls or slugs packed tightly into a canvas bag. The grapeshot was devastatingly effective against charging troops. Another new ammunition was the Minié ball, which was a conical-shaped bullet made of soft lead. When fired, the bullet engaged the barrel’s rifling, providing spin for better accuracy and longer range.

Like many other Civil War technologies, these weapons were available to Northern troops. The Southern factories had neither the equipment nor the expertise to produce such weapons.

The Confederates developed naval mines and torpedoes to counteract the Union’s blockades of Southern ports, which were very effective in sinking Union ships.

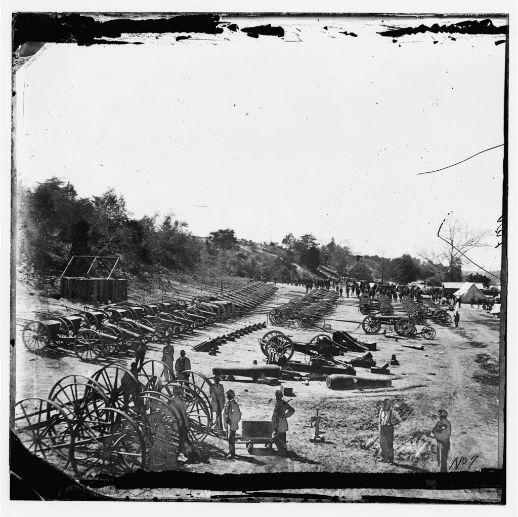

Confederate forces, which had a stronghold on Petersburg, settled inside the city while the Federal troops surrounded them to the south and east. The Union Army set up numerous supply depots to bring in ammunition in preparation for the siege. An important depot was established in the town of Broadway Landing, located eight miles northeast Petersburg, Virginia. This photograph shows how extensive the amount of weapons was, emphasizing Broadway Landing’s importance, and the crucial role it played during the Siege of Petersburg and in winning the war.

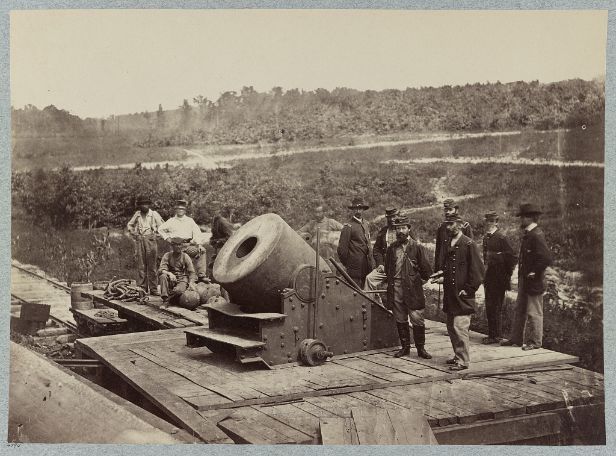

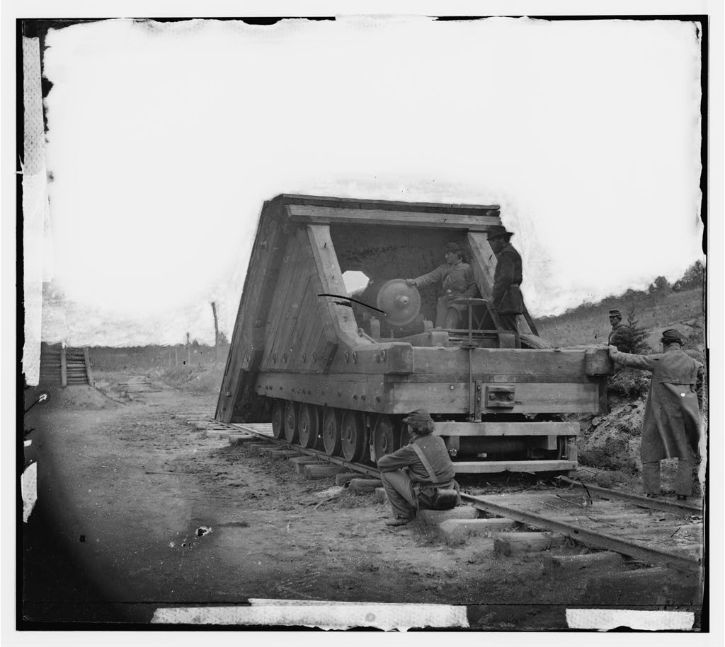

The most famous mortar used during the war was the “Dictator.” This weapon was a 13- inch, Model 1861, seacoast mortar which was mounted on a specially reinforced railroad car to accommodate its weight of 17,000 pounds.

Company G of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery operated the “Dictator” at the siege of Petersburg, Virginia in 1864. The mortar could fire a 200-pound explosive shell about 2.5 miles. The “Dictator” was usually positioned in a curved section of the Petersburg and City Point Railroad and was employed for about three months during the siege.

Railroad guns earned an unequaled reputation by terrorizing civilians, firing on cities without warning from afar. Confederates mounted a 32-pound naval rifle to a flatcar protected by an iron casemate. The finished car looked like a land version of the ironclad. The Union used a similar railroad mounting during the 1864 Siege of Petersburg.

New technologies developed during the Civil War increased the killing power of weapons. The results were casualty rates far greater than the estimations of military medical planners. The deployment of troops over large areas of the country also made it difficult for the wounded to be located and evacuated. The large number of sick and wounded forced the army to develop more efficient treatments and technologies to prevent death.

In 1861, the United States government authorized the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) to provide medical and sanitary assistance to Union forces. The USSC conducted hospital inspections; assisted with food, clothing, and medicine; and worked to improve the transport of wounded soldiers.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the Sanitary Commission continued negotiating the return of prisoners of war and caring for hospitalized soldiers. The commission’s active relief work officially ended on October 1, 1865, but its impact still reverberates.

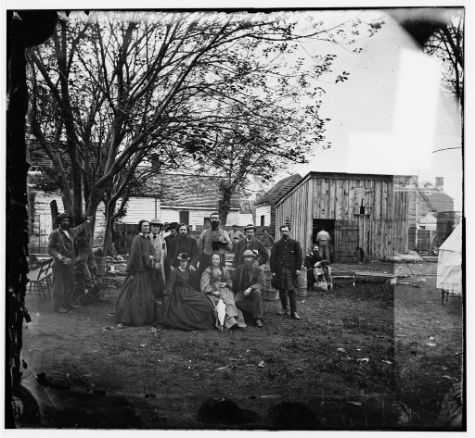

This photograph is from the main Eastern Theater of the Civil War, taken during Grant’s Wilderness Campaign between May and June of 1864.

The woman seated in center with the umbrella is volunteer nurse Abby Hopper Gibbons of New York City with her daughter, Sarah Hopper Emerson Gibbons, seated to her left. Abby Hopper Gibbons was born a Quaker in Philadelphia. In 1833, she married James Sloan Gibbons of Wilmington, Delaware, and they became important activists in the abolitionist movement in New York City in the decades before the Civil War.

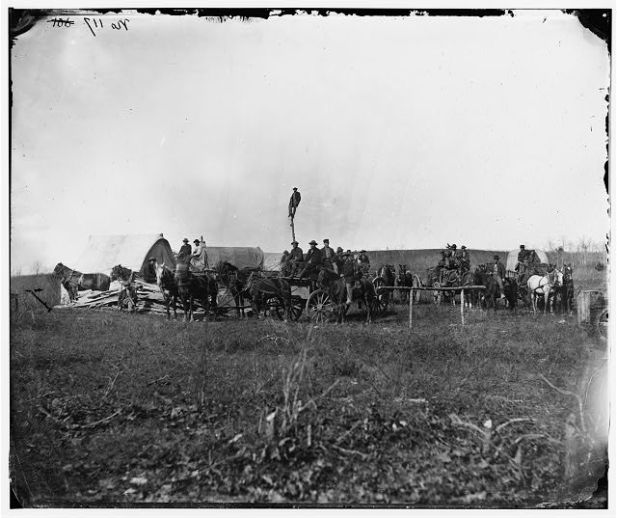

During the Civil War the ambulance-wagon saved thousands of lives. This photograph illustrates the use of one of the three most common ambulances used during the war. This model is the lighter “Rosecrans” or “Wheeling” model. This model began to be used around the time of Fredericksburg and generally replaced the earlier models by the end of 1863.

At the beginning of the Civil War, medical equipment and knowledge hardly met the needs posed by the wounds, infections, and diseases that affected both sides. One third of the approximately 620,000 soldier deaths in the war were the result of enemy fire. The other two thirds were the result of disease. These statistics pushed American doctors to develop efficient medical practices.

Surgeon General William Hammond designed clean, well-ventilated hospitals where soldiers were treated. His influence led to advanced hospital care. At the start of the war, the mortality rate for secondary infections was sixty-two percent. By the end of the war, it had fallen to three.

The Hospital Directory was established to address concerns

of families inquiring about their loved ones. It also served as a data- collection

center for the Statistical Bureau for the evaluation of medical performance. Through

the evaluation of collected data, the Sanitary Commission better understood the complexities

of caring for soldiers.

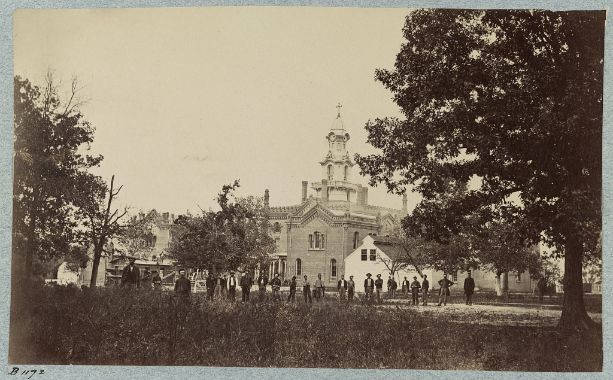

This photograph shows a group of men, some in uniform, standing in front of the Fairfax

Seminary, which served as headquarters for the Army of the Potomac. The seminary housed

an overwhelming 1,700 sick and wounded soldiers during the course of the war.

The great American poet and Civil War nurse, Walt Whitman, described these improvised

hospitals in his memorandum as “merely tents, and sometimes very poor ones, the wounded

lying on the ground, lucky if their blankets are spread on layers of pine or hemlock

twigs or small leaves.”

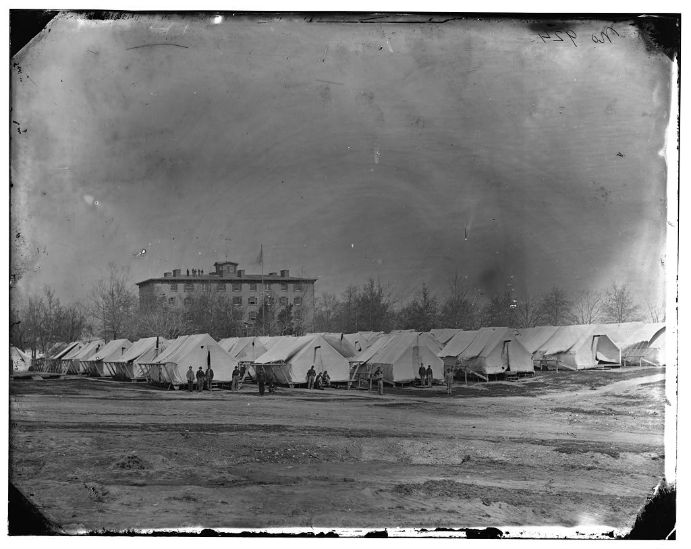

The Armory Hospital was a military hospital used by the Union Army. It was built in 1862 and operated until 1865. It had 1,000 beds in twelve pavilions and overflow tents. The hospital had a chief surgeon in charge, with each ward having its own surgeon and female nurse, ward master, cadet surgeon (to dress wounds), three attendants, and two night watchmen. The quality of care in hospitals improved due to the high volume of procedures performed daily. President Abraham Lincoln visited the hospital often.

During the Civil War, thousands of physicians received experience and training in field hospitals. The high numbers of sick and wounded helped doctors and nurses to improve anesthetics, surgical practices, and the treatment of infectious diseases. With these advancements, medicine was thrust into the modern era of quality care.

Most eye injuries were caused by gunshots and the fragments of shrapnel and dirt that soldiers were exposed to during combat. The large number of eye injuries contributed to rapid developments in ophthalmology, including the invention of the ophthalmoscope which allowed doctors to look into the eye.

Although thousands of women served as volunteer nurses during the Civil War, their service was mostly unrecorded, with the exception of a few famous women including Louisa May Alcott, Jane Stuart Woolsey, Susie King Taylor, Katherine Prescott Wormeley, Clara Barton, and Dorethea Dix. Barton and Dix organized a nursing corps to help care for wounded soldiers. Later, Clara Barton founded the American Red Cross. Louisa May Alcott, known worldwide as the author of Little Women, also served as a volunteer nurse.

Walt Whitman, the world-renowned writer and poet, became a nurse when his brother was wounded in 1862. Whitman went to Fredericksburg, Virginia, to care for him. After he saw the battlefield, he volunteered to care of soldiers and worked as a nurse in Washington, D.C. for eleven years.

Religious orders sent their trained nurses to staff field hospitals near the front. Within a few months of the start of the war, 600 women were serving as nurses in twelve hospitals. Eight Catholic orders sent nuns to serve in the war. At the beginning of the war, the nursing profession was dominated by men. Because nurses of the Civil War made a significant difference, both the public and the medical communities finally came to recognize nursing as a legitimate profession.

Born in Massachusetts in 1821, Clara Harlowe Barton moved to Washington, D.C. in 1854. She was employed as a clerk in the Patent Office until 1857. Barton worked among soldiers in the field from the beginning of the Civil War. She brought medical supplies with her in three army wagons and gave aid to Union casualties and Confederate prisoners. Barton solicited donations to purchase most of the supplies. As founder of the American Red Cross, Clara Barton brought professional efficiency to soldiers in the field. She died in 1912 at the age of 91.

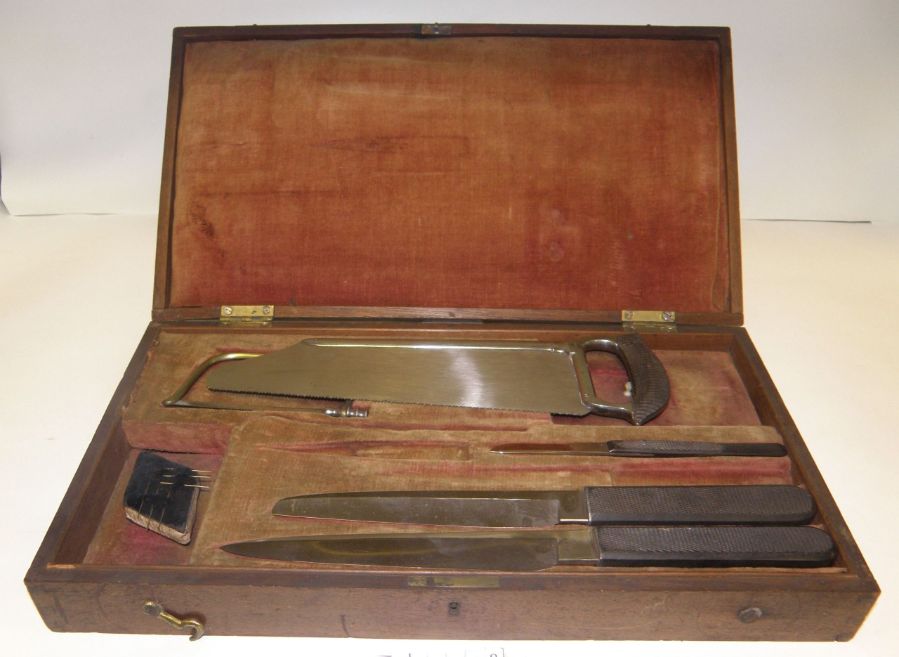

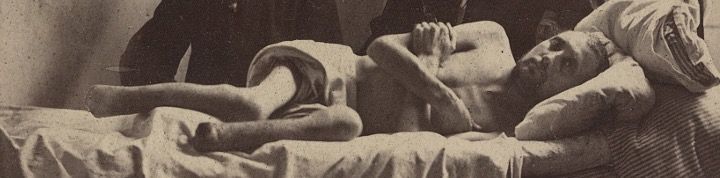

The advancement of weapons during the Civil War contributed to a large number of amputations and new surgical procedures. A bullet fired from a smooth-bore would often be deflected by the larger bones of the body, and would not inflict significant injuries. The introduction of the rifled musket and the Minié ball resulted in horrific injuries with massive tissue destruction and crushed bones.

Amputations became the most common surgical procedure during the Civil War. Almost 30,000 amputations were recorded by Union surgeons. A similar number is expected to have been performed by Confederate surgeons. This did not include the amputations performed in hospitals, or the ones performed during the chaos at the beginning of the war.

Undoubtedly, amputations saved numerous lives. Surgeons on both sides learned from the numerous cases and made continuous improvements. The multitude of amputations contributed to advancements in the field of rehabilitation medicine and the rapid development of prosthetics.

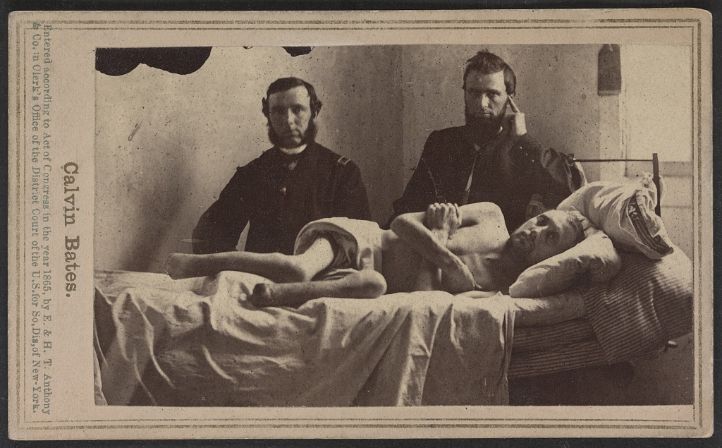

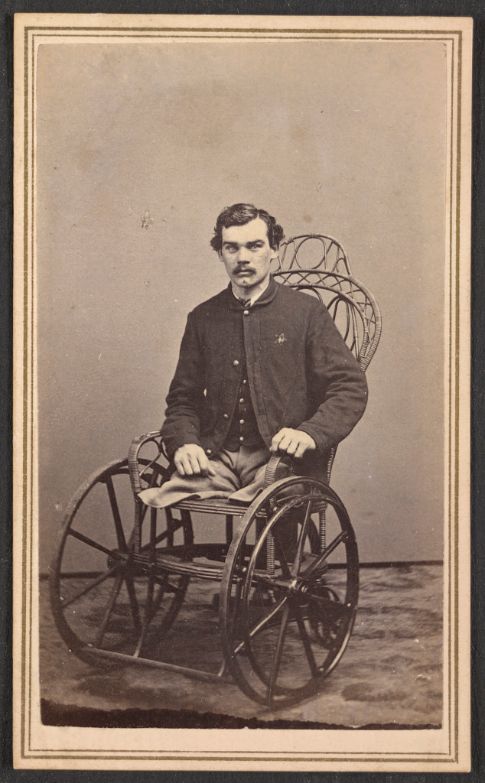

This photograph shows Corporal Calvin Bates of Company E, 20th Maine Infantry Regiment. He was captured at the Battle of the Wilderness and ended up in Andersonville, Georgia. While captured, he was subjected to inhumane treatment and had to have both feet amputated as a result.

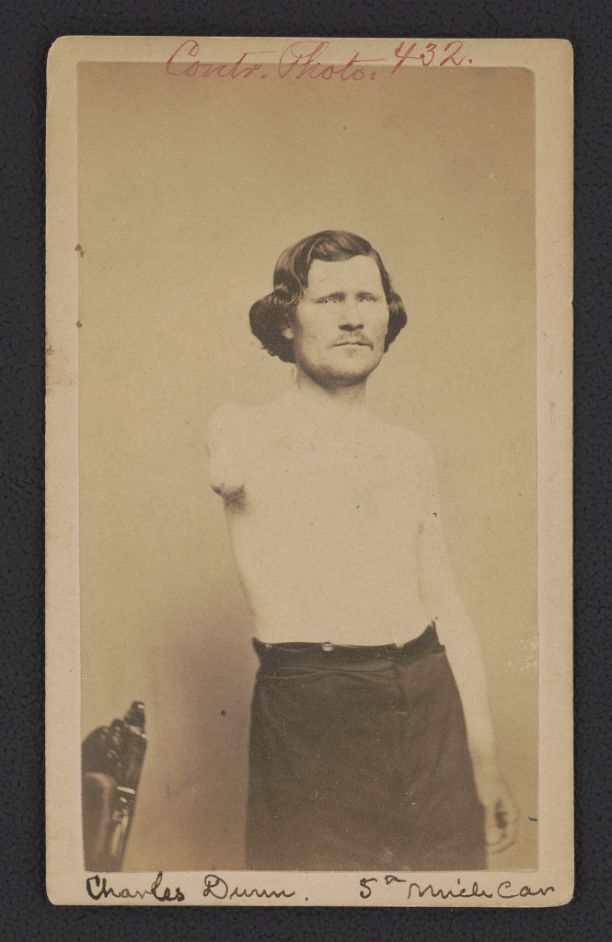

Private Charles Dunn of Co. L, 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment, was severely wounded at Newtown, Virginia, on November 12, 1864, which resulted in the amputation of his right arm. Many photographs of soldiers with amputations were taken shortly after the conclusion of the war in 1865 and show the shocking brutality of America’s Civil War.

This photograph shows portrait of Corporal Michael Dunn of Co. H, 46th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, after the amputation of his legs in 1864. He received injuries in a battle near Dallas, Georgia, on May 25, 1864. Dunn also fought at Gettysburg, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. After the war, he wrote about his injuries and repeated amputations. (Source: “One Hell of a Life,” by Donald Gilliland, Mountain Home, May 2011)

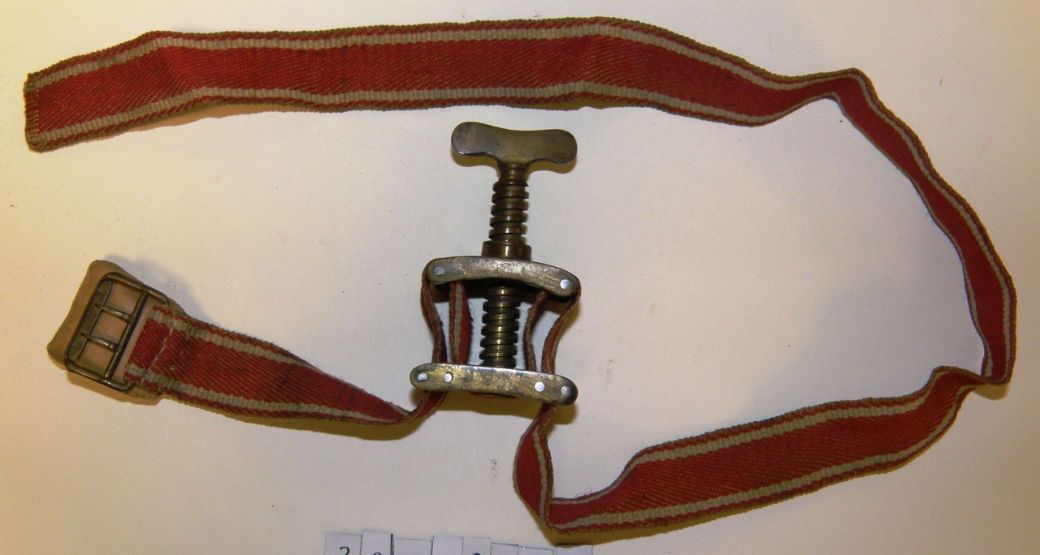

The limits of mid-nineteenth century medicine and the severity of the wounds sustained by soldiers resulted in a large number of amputations.

Tourniquets were used to compress arteries above the cut during amputations.

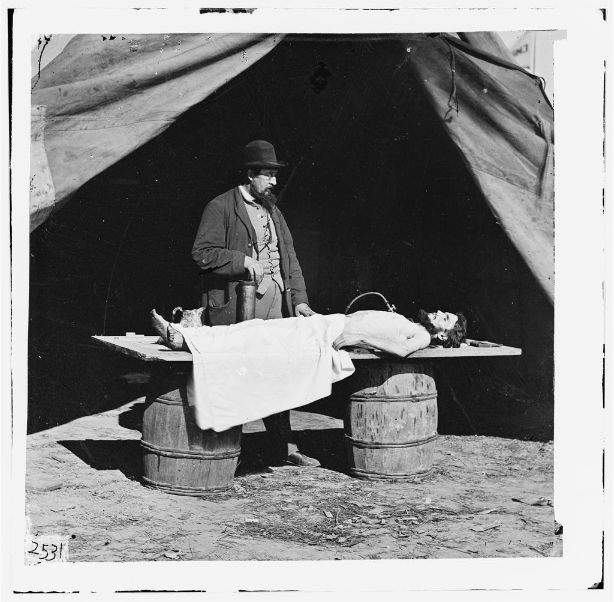

In 1838, French chemist, Jean Gannal, introduced a method for preserving human remains which consisted of injecting arsenic into the carotid artery. Dr. Thomas Holmes (1817-1900), who worked as a coroner’s physician in New York in the 1850s, started embalming using the French methods.

Embalming was not a common funerary practice before the mid- 1850s. It all changed after the start of the Civil War when Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth (1837-1861) was shot while removing a Confederate flag from the roof of the Marshall House Hotel in Alexandria, Virginia. Thomas Holmes offered his services to the Ellsworth family, making it possible to have the body taken to Washington, D.C. and New York in the course of ten days before the burial. As a result of this successful embalming, the Army Medical Corps allowed Dr. Holmes to embalm dead Union officers before they were sent home for burial. This marked the beginning of a new industry, as the Civil War created a need for handling the bodies of soldiers and officers who died far from home.

Over the course of the war, Holmes himself embalmed more than 4,000 men at a cost of $100 per corpse. He also sold the fluid he created for the procedure. The high number of casualties during the Civil War contributed to the establishment of the American funeral industry.

In this photograph, Dr. Richard Burr, a nineteenth century Army surgeon who established a flourishing practice of embalming fallen Civil War soldiers, embalms a deceased young man upon a makeshift table. A large number of civilian surgeons at the time also practiced embalming.

Abraham Lincoln was the first president of the United States to be embalmed. His funeral train left Washington, D.C., on April 21, and arrived in Springfield, Illinois on May 3, 1865.

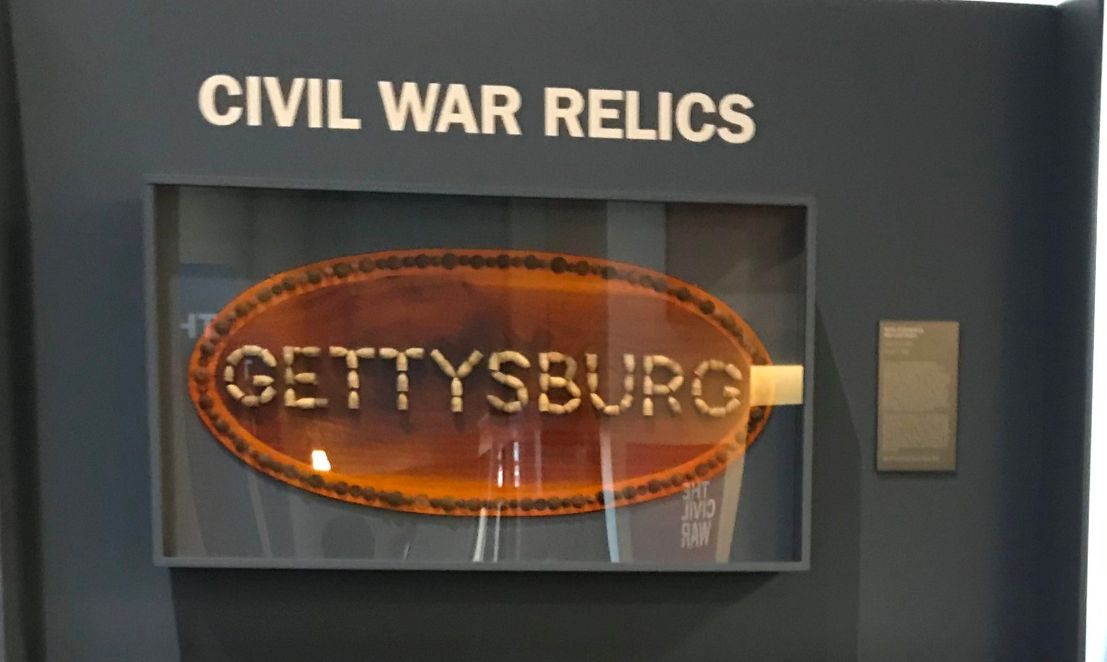

This oval, wooden plaque spells out “Gettysburg” using expended Minié balls and a round shot recovered from the battlefield. During the Civil War, the Ordinance Department purchased more than 470 million Minié balls. A Minié ball is a .58 caliber bullet of French design made of lead with three grooves and a cavity at the base. The round shot is likely from canister rounds fired by a cannon. Pickett’s Charge on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg was largely broken as a result of the heavy casualties incurred by Union artillery firing canister shots.

The plaque is bordered with recovered brass US General Service Eagle buttons depicting a spread eagle and lined Union shield. These buttons were used on sack coats – the deep blue jackets – worn by Union enlisted soldiers. Three buttons feature a Union eagle and the word “Excelsior,” the state motto of New York. Two buttons feature an “I,” indicating infantry. Several shirt buttons are also incorporated in the border.

Displayed are four muskets all of which are were used by Federal and Confederate armies during the Civil War. The U.S. Model 1842 musket was manufactured at the Harpers Ferry Arsenal in Virginia while the U.S. Model 1855, U.S. Model 1861, and the U.S. Model 1863 muskets were produced at the Springfield Arsenal in Massachusetts.

- The U.S. Model 1842 musket was the last of the smooth-bore muskets and fired a .69 caliber ball. More than 275,000 were made and it was the first musket to use percussion caps to fire the loaded gunpowder rather than using flint to spark gunpowder that a soldier would have charged onto a musket’s frizzen (plate). It was also the first musket to incorporate interchangeable parts throughout meaning that the musket could be easily repaired and returned to service. Many of these muskets were later converted by rifling the barrel. This musket was never converted.