Race and Representation: Euro-American Depictions of Native Americans and Their Cultures

Race and Representation: Euro-American Depictions of Native Americans and Their Cultures is a joint effort of the art history course ARTH 4900 Research Methods and the Saint Louis University Museum of Art, and was inspired by the recent donation of art and historical artifacts to the University by Timothy and Jeanne Drone. The exhibition opened at SLUMA on December 7, 2018 and remained on view until May 26, 2019.

Race and Representation presents a selection of nineteenth-century Euro-American lithographs of portraits, activities, and rituals of Indigenous North Americans from the perspective of postcolonialism, a methodology for interpreting visual culture that brings the past and present results of imperialism to the foreground. Underscoring the reciprocating impacts that colonizers and the colonized have on each other, this exhibition seeks to provide a recontextualization of these images through the lens of Euro- and Native American relations.

Curated by associate professor of art history Bradley Bailey, Ph.D., and students Jordan Behenna, Nicholas di Napoli, Raegan Jackson, Braden Kirvida, Bailey McCulloch, Mary McGuire, Marguerite Passaglia, and Ela Sutcu, with the support of SLUMA director Petruta Lipan and registrar-collections manager Kathryn Reid, Race and Representation was conceived as an opportunity for advanced art history students to work directly with the University collection while benefiting from the experience of faculty and staff.

Race and Representation: An Exercise in Postcolonial Analysis

“First, it is not a study of other cultures. Looking at African masks or Australian aboriginal painting is not the same as postcolonial analysis. Postcolonial theory is concerned with something rather more specific: it deals with the interaction between imperial and indigenous cultures, most notably that between Western imperial nations and their colonies (but not exclusively). So rather than exploring other cultures as such, it looks at what happens to cultures when they meet, what the material effects of colonisation are, how the process of colonisation changes the ways people think, and act, and write, and paint, and so on.”

– Michael Hatt and Charlotte Klonk, Art History: A Critical Introduction

The United States government’s policies of acculturation, assimilation, and forced removal regarding the Native populations of North America from the Jefferson administration to the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 are an essential component of the Euro-American historical curriculum. Yet the awareness of the historical details of the American colonial enterprise and its impact on indigenous civilizations is only part of the practice of the postcolonial methodology used for research and the analysis of visual culture. Even more critical for the interpretation of visual culture from the postcolonial perspective is a deeper appreciation for the struggle over cultural and historical narratives that imperialism entails.

Therefore, it is imperative that when we look at the prints on display in this gallery, we recognize that we are looking at the diverse appearances, activities, and rituals of one race through the eyes of another. And while these images have been widely regarded as demonstrating a deep admiration and profound respect for the cultures being depicted, others have described them as romanticized, exploitative, and even racist. Whether or not these artists or the publishers of these images subscribed to the prevailing dogmas of Manifest Destiny and social Darwinism as the principal forces behind the severe reduction of the Native American population, their images do in many ways reflect the broader nineteenth-century Euro-American viewpoint of the Indigenous peoples of North America as “other.”

Further complicating the display of these images is that to focus on their aesthetic value at the expense of their historical context does a tremendous disservice to the cultural groups being depicted. Yet to disregard the historical importance and quality of these images is likewise a missed opportunity to better understand what it means to represent a subject, and how that subject is subsequently consumed by diverse audiences. This exhibition does not presume to resolve this complex dilemma, but rather to create a forum in which to view these images both as artistic endeavors and as historical artifacts that—when properly contextualized— constitute a valuable cultural resource.

This exhibition is also intended to demonstrate our appreciation for Timothy and Jeanne Drone, who possess not only the foresight and acumen to collect and preserve such artifacts and visual culture, but also the generosity to make a gift of them to the students, faculty, and staff of Saint Louis University.

|

HAYNE-HUDJIHINI Eagle of Delight, also known as Hayne Hudjihini (c. 1795-1822) in the Chiwere language, was a young wife to Shaumonekusse, an Otoe chief. Said to be the favorite of Shaumonekusse’s five wives, Hayne Hudjihini accompanied her husband to Washington D.C. in 1821, where she reportedly captivated all who met her, including President James Monroe. According to the official White House website of President George W. Bush, she was stricken with measles during her visit, and she died soon after her return to her homeland. Although Hayne Hudjihini’s face is uniquely portrayed, it appears as if her other features are generalized. Her clothing, jewelry, and hairstyle appear extremely similar to other female Native American portraits done by Charles Bird King. King’s personal copy of her portrait now hangs in the White House Library. |

|

|

CHON-MON-I-CASE Chonmonicase, or Shaumonekusse (c. 1785-1837), also known by the name Prairie Wolf, was a chief of the Otoe tribe. Among the first Natives to encounter the Lewis and Clark expedition, the joint tribe of Otoe-Missouria gradually ceded most of their lands along the Missouri River to the United States by way of various treaties. By 1855, the Otoe-Missouria were completely confined to a reservation along the Big Blue River in Nebraska, where they struggled to survive and maintain their traditional way of life. Shaumonekusse was one of a number of Native dignitaries to meet with President James Monroe in Washington D.C. in 1821. Charles Bird King’s portrait depicts him wearing a headdress decorated with bison horns (see wall text panel in this gallery). His peace medal is a stark reminder of both this meeting and the treaties that led to the loss of his people’s land. |

|

|

ME-TE-A This lithograph portrays the courageous warrior and an esteemed leader Chief Metea (d. 1827) of the Potawatomi tribe, which was once located throughout the Great Lakes region. An influential spokesperson, Metea negotiated not only in defense of his own tribe at the signing of the Treaty of Chicago in 1821, but on behalf of the Chippewa and Ottawa tribes as well. In 1829, the Treaty of St. Joseph ceded the remainder of the Potawatomi land to the U.S. government, and the people were relocated to Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Descriptions of Metea suggest that he was highly respected by both his people and Euro-Americans alike. His alleged alcoholism, which supposedly and indirectly caused his death when he was said to have mistakenly consumed nitric acid thinking it was liquor, fed into the racial myths and stereotypes surrounding Native peoples and alcohol consumption. Others believe that he was actually poisoned for being too outspoken against land cessations. |

|

|

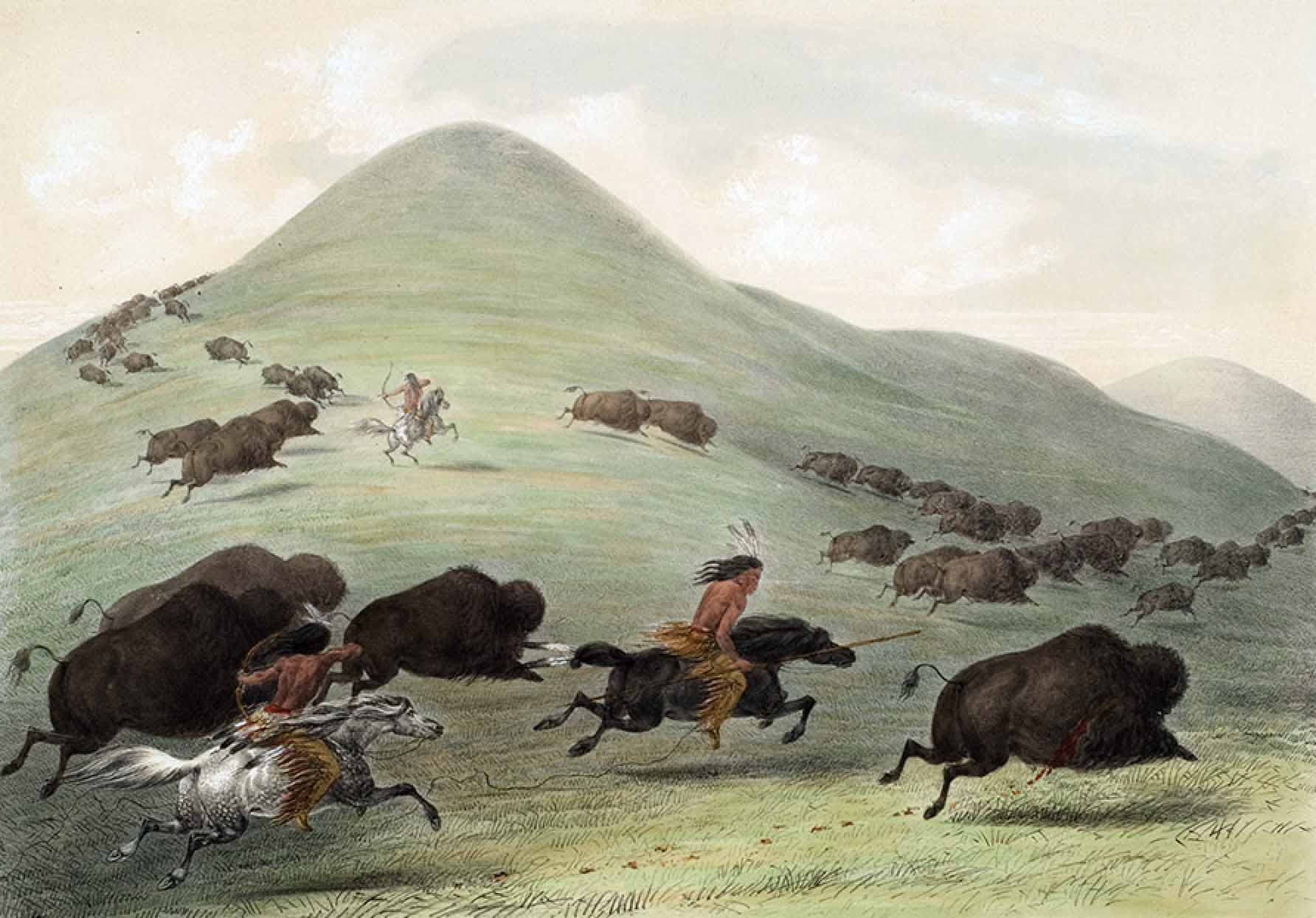

Buffalo Hunt, Chase |

|

|

Buffalo Hunt, Surround |

The Ball Game

In 1834, George Catlin witnessed the Choctaw tribe stickball game, which he depicted in two paintings that were subsequently reproduced in the lithographs seen here. The ball game was seen in the community as a way for individuals to distinguish themselves within the tribe, as well as a means of settling disputes within the tribe or between tribes. Before the game, the athletes would participate in ritual dances and songs for good luck. In Ball Play Dance, the players and other tribe members are neatly organized in groups that represent the spiritual nature of the pregame rituals that functioned as a form of collective worship. In contrast, Ball Play is more chaotic, emphasizing the potential of the game as a means for an individual to stand out in the tribe. Indeed, as a form of symbolic combat, competitors played fiercely for personal and tribal glory in games that could last up to several days.

While stickball is perhaps better known today for its reputation as the wild, violent precursor to modern lacrosse, the original game is still played today and remains a vital part of Choctaw culture. The World Series of Stickball takes place at the annual Choctaw Indian Fair in Choctaw, Mississippi, where multiple divisions of men, women, and youths compete using traditional equipment. In recent years, teams comprised of the descendents of relocated Oklahoma Choctaws and Chickasaws have challenged the Mississippi Choctaws at the annual fair, revitalizing the sport at the national level. The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations were two of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” due to their perceived willingness to adopt Euro-American attributes.

|

Ball Play |

|

|

Ball-Play Dance |

|

|

Kapucha (sticks) and towa (ball) In the Native American game of stickball, opponents use wooden sticks called kapucha, seen here, with a basket-like head to juggle, catch, and throw the ball or towa, also featured. The ball on display here is only the core, which was encased in stitched hide stuffed tightly with a variety of materials, including deer hair, thread, or rags. In the double-stick version of stickball played by tribes located principally in the southeastern part of the present-day United States, players sandwich the ball between the cups of their sticks to protect it from the other competitors. The equipment used in stickball varies by region, including a single-stick version of the game that flourished in the northeast and Great Lakes areas. The latter version was the one adopted by non-Native players in areas around the U.S.-Canadian border, which in time evolved into the modern game of lacrosse. |

|

|

The Bear Dance This vibrant scene portrays the Bear Dance ceremony as performed by members of the Sioux tribe that George Catlin encountered during his Western expeditions. The omission of any background or surrounding environment directs all attention towards the vivid ritual. A medicine man leads the dance, and is distinguished with a complete bear pelt and mask in the foreground. Such ceremonies preceded bear hunts that, if successful, provided sustenance for weeks to come. According to Catlin’s lucid description of the ceremony: Many others in the dance wore masques on their faces, made of the skin from the bear’s head; and all, with the motions of their hands, closely imitated the movements of that animal; some representing its motion in running, and others the peculiar attitude and hanging of the paws, when it is sitting up on its hind feet, and looking out for the approach of an enemy. It is noteworthy that the medicine man wears a peace medal like those exhibited in this gallery, as well as those worn in the portraits of Black Hawk and Shaumonekusse. The medal is a startling reminder of Euro-American presence in a scene depicting such traditional activity, and speaks to how deeply European influence had penetrated into Native culture. The Bear Dance exemplifies the controversial nature of Catlin’s Indian Gallery, his touring collection of portraits, landscapes, and scenes of Native American life, as it both recorded images of a rapidly diminishing way of life for posterity, but also emphasized the deviance of such ceremonies from the rapidly spreading Euro-American Christian norm. |

Object In Focus

|

Bison horn headdress Great Lakes, North America This rare headdress of the Great Lakes region is in the collection of the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain. It is a type of headdress reserved solely for warriors of the highest rank, such as the Otoe Chief Shaumonekusse, whose portrait is exhibited in this gallery. It is constructed from bison hide and colorfully decorated with dyed porcupine quills and horse hair. It is adorned with two hollowed-out bison horns, which are polished and finished at the tips with locks of horse hair. This variety of headdress was worn for the functional purpose of easily distinguishing the leader from other warriors. In his two-volume book Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, first published in 1841, George Catlin described such a piece: “There is occasionally, a chief or a warrior of so extraordinary renown, that he is allowed to wear horns on his head-dress, which give to his aspect a strange and majestic effect.” The Museo de América, built in Madrid in 1941, houses the old archeological and ethnographic collections of Spain’s National Archeological Museum. Specializing in both pre-Columbian and colonial cultures, the collection features more than 25,000 artifacts from the Americas as seen from a Spanish imperialist perspective. Madrid is also home to Saint Louis University’s European campus, where art history is included among the 14 undergraduate degree programs that can be pursued entirely in Spain. |

|

|

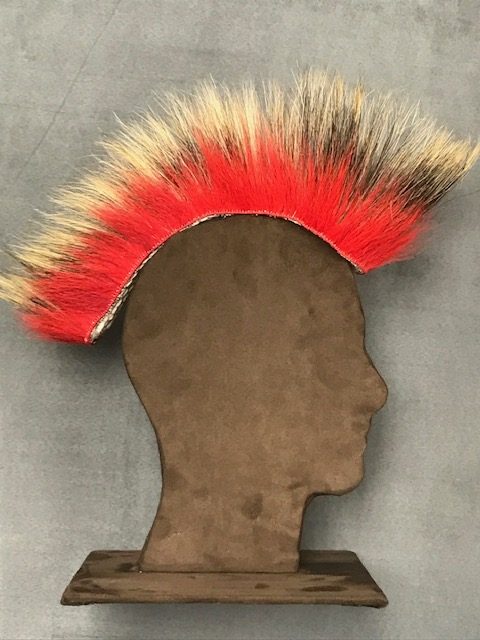

Roach (headdress) The head roach, a type of Native American headdress, is the most commonly used headdress among Native North American tribal groups. Most are made of some combination of animal hair, including porcupine, deer tail, moose and, in some areas, turkey beard fibers. Roaches are worn exclusively by men, and their use varies depending on the tribe. In some tribal customs, roaches are worn into battle, while in others they are worn as dance regalia or athletic dress. The exact origins of the head roach are unclear since it was so widely used, but some tribal traditions suggest the roach was an imitation of the red crest of the pileated woodpecker. The bright red color of some roaches, like the one depicted in the portrait of Black Hawk seen in this gallery, represents experience in battle. |

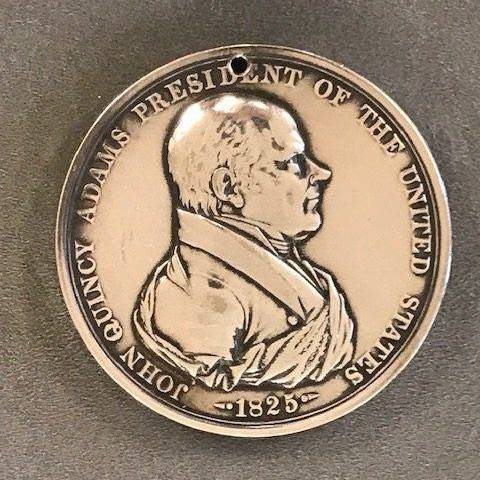

Indian Peace Medals

Peace medals were traditionally given to prominent Native Americans by Euro-American and European colonizers to seal alliances. The peace medals shown are from a collection of United States presidential medals, which were originally cast in silver using engraved dies. These medals depict presidential portraits on one side and an image of a U.S. soldier and a Native American shaking hands on the other. The handshake is accompanied by the inscription “Peace and Friendship” along with a crossed tomahawk and pipe. The medals were created in three sizes, the largest reserved for chiefs and other dignitaries. While the awarding of these peace medals to Native Americans represented alliances with the U.S. government, they did not guarantee harmony. Following 1842, bronze replicas of the original Presidential medals were created for presentation to historical societies or government officials.

John Quincy Adams Indian Peace Medal

Likely restrike of 1825 original

Obverse: Moritz Furst (Slovak-American, 1782-1840)

Reverse: John Reich (German-American, b. Johann Matthias Reich, 1768-1833)

Silver-plated copper

Gift of Timothy and Jeanne Drone, 2018

Original silver peace medals given to Native Americans by the United States government are exceedingly rare, and those that were worn by chiefs and warriors typically show significant signs of wear. The medal on view here is likely a copper restrike created for collectors by the U.S. Mint that was subsequently silver-plated by profiteers for trade with the Native population, a practice that began in the late nineteenth century. Careful examination of the interior of the hole reveals a small patch of copper underneath the thin layer of silver plating.

George Washington Indian Peace Medal

Restrike of 1789 original

Obverse: Pierre-Simon-Benjamin Duvivier (French, 1730-1819)

Reverse: John Reich (German, b. Johann Matthias Reich, 1768-1833)

Yellow bronze

Gift of Timothy and Jeanne Drone, 2018

The size and material of this medal, along with the combination of imagery on the

front and back, suggest that it is a version that was first made as early as 1903

to complete the set of bronze replicas of presidential medals that began with the

restrike of the original 1801 Thomas Jefferson peace medal in 1842. This particular

Washington peace medal on view is exceptional in that it has a loop at the top for

wearing, which is an unusual feature as the replicas were for collectors only and

never intended to be worn by Native American dignitaries. Despite the misleading name

“yellow bronze,” the material is actually an alloy consisting largely of copper.